______________________________________________________________________________________________________

This is a guest post by Lottie Park-Morton, Senior Lecturer in Law at University of Gloucestershire, who is currently undertaking a PhD on surrogacy and children’s rights. Lottie tweets as @cparkmorton

Two recent cases, in which Theis J granted legal parenthood to intended parents following a surrogacy arrangement, add to the existing body of case law demonstrating the need for a reform of the law relating to parenthood following surrogacy arrangements. In Re Z (A Child) (Surrogacy) [2022] EWFC 18 and X v Z (Parental Order: Adult) [2022] EWFC 26, the court was again asked to interpret the statutory provisions in such a way as to give legal recognition to the relationship between parent and child and to meet the welfare interests of the child.

Establishing legal parenthood following surrogacy

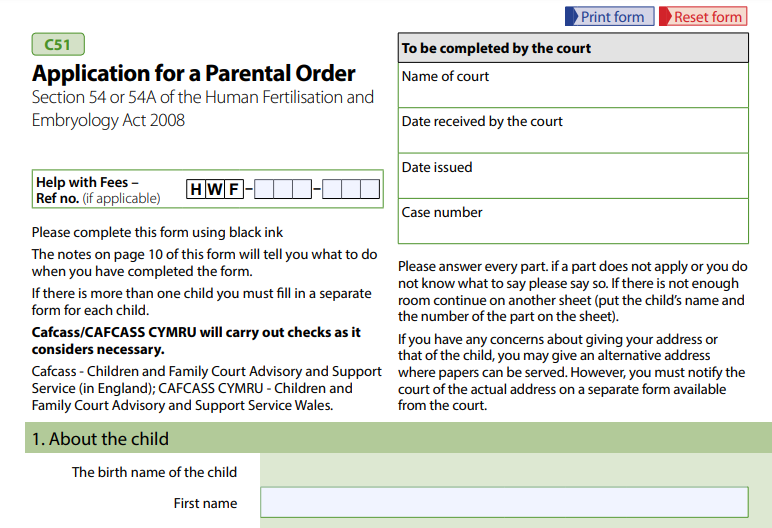

Currently in England and Wales, the surrogate – being the woman who carries the child to term and gives birth to the child – is the legal mother of the child. In order for the intended parents – being the individuals who commission the surrogacy arrangement and intend to act as the parents of the child – to be recognised as the legal parents, a s54 parental order must be sought. Upon the granting of a parental order, the surrogate’s legal parenthood is removed and the intended parent(s) are given status as the legal parents when a parental order certificate is issued.

There are several requirements for a parental order under the legislation, including that at least one intended parent be genetically related to the child, the child’s home must be with the intended parent(s) and the surrogate must consent to the granting of the parental order. However, since 2010 the court, when deciding whether to grant a parental order, is required to consider the welfare of the child throughout their life as a primary consideration. The effect of importing this welfare consideration from the adoption legislation has led to lots of case law which sees the courts working hard to interpret the s54 requirements in order to allow a parental order to be granted in line with the child’s welfare.

The landmark case of Re X (A Child) (Surrogacy: Time Limit) [2014] EWHC 3135 (Fam) opened the doors to the liberal interpretation of the parental order requirements, granting a parental order outside the stated 6-month time limit under s54(3) on the basis that the child’s identity and welfare necessitated the parental order to be granted. Since Re X, a similar approach has been adopted to various s54 requirements, including the requirement for the intended parents to be in an ‘enduring family relationship’ and for the child’s home to be with the intended parents. The extent to which the judiciary have stretched, arguably to breaking point, the s54 requirements has led many to question the continued relevance of some of these provisions.

The recent judgments handed down by Theis J continue in a similar vein, and reaffirm the imperative of law reform in this area.

Re Z (A Child) (Surrogacy)

During care proceedings relating to Z, it became apparent that Z had been born through surrogacy, resulting in care proceedings being stayed whilst a parental order application was made. The circumstances around the commencement of the surrogacy arrangement was unclear, with contradictory accounts from both applicants as to the involvement of the mother in the arrangement and the payments made to the surrogate who was living in Georgia.

In considering the s54 requirements, both intended parents were genetically related to the child, the applicants were domiciled in England and Wales by choice, and the surrogate – after a lengthy period of trying to locate her – provided her consent to the granting of the parental order. These requirements were therefore satisfied without difficulty.

In line with Re X and subsequent cases, the expiration of the 6-month time limit did not affect the ability to grant the parental order. The remaining s54 requirements did, however, require further exploration. In relation to payments made to the surrogate, despite a lack of clarity as to how much the intended parents had paid, Theis J approved the payments on the basis that they did act in good faith and did not try to get around the authorities when making the payments [para 61].

The remaining requirements, for the intended parents to be married or in an enduring family relationship and for the child’s home to be with the applicants, were affected by the nature of the marital breakdown between the applicants, thus meaning the child was living with the mother only. However, drawing on previous cases that had taken a broad and purposive interpretation to these requirements, Theis J found that, in line with Article 8 of the European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR), de facto ‘family life’ had been established and thus these requirements, too, had been satisfied.

Whilst finding that all of the s54 requirements had been met, or could be interpreted in such a way as to allow for the granting of the parental order, the welfare of the child remained a paramount consideration.

In granting the parental order, Theis J gave weight to Z’s relationship with his siblings, as well as the intended parents, stating:

Notwithstanding the finding that granting a parental order would be in Z’s best interests, Theis J was critical of how the intended parents’ conduct could affect Z’s welfare. The inconsistent accounts of the circumstances leading up to the surrogacy arrangements, including the mother’s role in providing gametes (i.e. her eggs) and consenting to the arrangement, led Theis J to state:

This case therefore demonstrates that, although intended parents may not always act in a way which consistently protects the welfare of the child, this will not in itself prevent the granting of a parental order if the child’s overall welfare, throughout his life, would be met by recognising his social parents as his legal parents.

X v Z (Parental Order: Adult)

In this case, the parental order related to Y, a surrogate-born individual born in 1998 and, therefore, an adult. Throughout the legislation, reference is made to the order relating to a ‘child’, and it was a novel issue for the court in that a parental order had never before been sought in relation to an adult. However, all parties – including the intended parents, surrogate and surrogate-born individual – were not aware until last year that the American birth certificate, naming the intended parents as the legal parents, was not effective in England and Wales.

Considering the s54 requirements in general, Theis J was satisfied that most of the requirements had been met. There were two requirements, however, that needed further exploration.

In relation to the requirement for the child’s home to be with the applicants, Y was no longer living in the family home. However, in a similar interpretation as Re Z, discussed above, Theis J was satisfied that in taking a ‘broad and purposeful interpretation’ of the provision, ‘their family lives remain entwined and inextricably linked’ and was thus satisfied that Y could be said to have his home with the applicants [para 49]. As for the 6-month time limit, drawing again on the leading case of Re X, Theis J was satisfied that the application exceeding 6-months, and in fact 24 years after the birth of the child, would not prevent the ability to grant a parental order so as to give effect to the reality of their lives and to give lifelong security to the individual.

The judge was satisfied that, apart from the references throughout the legislation to ‘child’, the s54 requirements were satisfied, and so considered whether a parental order could be granted to an adult. Drawing on the submissions made by counsel, it was suggested that there was no explicit prohibition on a parental order being granted to someone exceeding 18 years old, which can be contrasted with the Adoption and Children Act 2002 and Children Act 1989 which explicitly prevent an adoption or child arrangements order being made in relation to an individual who has reached either 16 or 18 years old.

Theis J was of the view that the legislation did not prevent her from granting an order in respect of Y’s legal parents. Further, if that interpretation of the HFE Act 2008 was incorrect, she also stated that the Human Rights Act 1998 required the court to interpret the legislation to give effect to Y’s right to respect for family life with his parents, including his identity.

Throughout the judgment, reference was made to the significance of the parental order in terms of both their family life, as a family unit, as well as the individual’s identity as an aspect of his private life, protected under Article 8 of the ECHR:

Therefore, the judge relied heavily on the rights as contained within the ECHR of both Y and the applicants, and the parental order was granted, recognising the intended parents as the legal parents of Y. Whilst some of the consequences of legal parenthood would no longer apply to Y as an adult (e.g. the exercise of parental responsibility) the allocation of legal parenthood remains significant for many practical reasons, as well as the more intangible, yet equally important, reasons of identity and familial connection. As Theis J insightfully stated in relation to the lack of consideration of granting legal parenthood to adults:

This perhaps reflects that as a matter of fact everyone remains the child of someone, even when they become adults [para 55]

Comment

Whilst Re Z (A Child) (Surrogacy) mainly reaffirms the approach of the judiciary to the relevant s54 requirements, the judgment remains significant in exemplifying how the child’s welfare must be considered. The intended parents’ conduct throughout the proceedings was questionable, and yet it remained the case that Z’s welfare was best met by having the intended parents recognised as his legal parents. Although Theis J raised concerns as to the impact the parents’ own conduct was also having on the child, the intended parents were the only parents the child had known and inevitably a parental order would need to be granted on the basis of the child’s welfare.

X v Z (Parental Order: Adult) is more novel. Never before has a parental order been granted in relation to an adult. This case takes statutory interpretation into a different sphere, substituting ‘child’ – as used throughout the legislation – and applying the provisions equally to an adult. The focus throughout the judgment on the individual’s identity, however, makes clear that, despite what the legislation might say, a parental order was necessary to provide the lifelong consequences that arise from legal parenthood.

The Law Commission is currently undertaking a review into the law on surrogacy following a period of consultation in 2019. The full report is expected in Autumn 2022, with provisional proposals to allocate legal parenthood to the intended parents at birth (with the surrogate’s right to object for a defined period). Should such a proposal be adopted, the various hurdles faced by the judiciary in the interpretation of s54 would be removed, allowing intended parents to more easily establish parenthood of the child; a reform that would operate in the interests of all parties involved, including the surrogate, intended parents, and most importantly, the child.

However, even if the law is reformed to ease this process, the role of the judiciary will remain – for surrogate-born children already born and yet to have their intended parents recognised as their legal parents, as well as in circumstances outside the new pathway to legal parenthood, such as when the surrogate objects or a cross-border surrogacy arrangement takes place. In such circumstances, it is essential that the judiciary are able to continue granting parental orders in order to meet the welfare and best interests of the child, and it is therefore vital that the s54 requirements are reviewed to ensure their continued relevance in the assessment.