“Delayed adoption is sure to damage a child“, writes Clare Foges for The Times (paywall). “Attempting to place children with family members has stalled the process to an alarming extent” says the subheader.

Here we go again.

For children who cannot stay with their birth families, adoption, and adoption at the earliest opportunity is a good thing. But we need to take care not to slip into simplifying that proposition into one which simply reads : Adoption is a GOOD THING.

Adoption is a means to an end (the welfare of the child). It is not an end in itself.

This article by Clare Foges, who writes compellingly and with experience of adoption and fostering within her family, begins by stating the former and ends by advocating the latter.

Foges sets out the potential harm cause by not removing a child soon enough and not securing a child in a permanent family. That is undisputable. She doesn’t however set out that in some adoptions the harm caused by becoming adopted, of not knowing or being part of the lives of the imperfect biological family, plays out in traumatic ways many years down the line, and that particularly for those children who suffered significant trauma before adoption all the love in the world cannot undo that harm. Adoption is no panacea.

Foges praises Michael Gove for the zeal with which he pursued and achieved a rise in adoption numbers. Not a reduction in adoption delay but a rise in absolute numbers of adoption:

The numbers adopted rose. Yet last week we saw for the second year in a row that adoptions in England have come down, despite the number of children in care increasing. The strides made by Gove have slowed to a limp. Why?

Why is the mere fact that adoption numbers have fallen a bad thing? Is it necessarily the case that the finding of alternative options for children is a BAD THING?

Lawyers reading this will know what comes next : this is all the fault of “a ruling in 2013” that stopped adoption zealots from achieving their goal of more adoption. That infamous ruling is the judgment of The Court of Appeal in Re B-S. Foges summarises Re B-S in this way :

Sir James Munby, president of the Family Division, implied to councils that adoption orders should be made only when there were no alternative options, such as placing the child with relatives. In the years since, in a giant case of Chinese whispers, this ruling has been misinterpreted by social services departments. It was taken as a dictum that adoption is always a last resort, that wherever humanly possible a child should stay in the care of those it is related to. This “family first” approach may sound reasonable, but there are unfortunate consequences.

Sir James did not imply adoption orders should be made only when there were no alternative options. He said it in legal terms (as did the rest of the Court of Appeal). Because it is the law. The law that pre-existed this ruling and the law that continues to apply in this country. The law that is consistent with a child and her parents’ rights to family life, that Parliament has approved.

Foges complains that the upshot of this is that

If blood is decreed to be so much thicker than water then social workers will be even more reluctant to take a child into care. All manner of “support” must be thrown at a family to keep it together; even if the parents are known to be on drugs and the child is clearly neglected. Still, they might benefit from mentoring and the odd visit from a social worker. And so truly disastrous parents drink in the last chance saloon for years, their children increasingly damaged. As Sir Martin Narey, a former chief executive of Barnardo’s and government adviser on care has said, the system is “gripped by an unrealistic optimism about the capacity of deeply inadequate parents to change”.

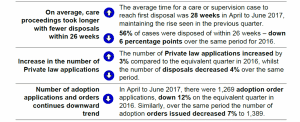

However, social workers do not seem to be more reluctant to take a child into care since 2013 because the numbers of care cases have been rising significantly for some time and are higher than ever (although the last quarter shows something of a plateau) and the number of looked after children is also on the rise. This is an odd thing to miss, given that the article is pegged on the release of statistics showing a reduction in adoption numbers published earlier this week that also contains the care numbers. It’s even on the same page (the LAC numbers are separate and can be found here but have also been widely reported as up).

Foges appears to be somewhat disdainful of the idea of supporting and fixing families so that children do not have to be removed, or so that the next sibling, the next baby born 18 months down the line does not have to be removed.

She says that :

The other consequence of the “family first” approach is that once it is decided a child’s future lies apart from its parents, instead of pursuing the adoption route, social services will first try to shake out every second cousin twice removed, in case they might care for the child. Staying with a blood relative is the priority, regardless of whether they offer a more stable home than adopters-in-waiting. Assessing relatives adds months to proceedings. Often one will pop up at the last hour to say they are willing to take the child. All this can cause huge delays, extending the wait for permanence.

Foges overstates the extent of what she calls the “family first” approach. Whilst it is true to say that the law demands that a child’s relationship with his family should never be completely severed through adoption unless the circumstances are exceptional and there is no other realistic option, the law does not say that there is a presumption in favour of family once the threshold for state intervention has been crossed. Put in more simple terms, if the court considers that a child has suffered significant harm or is at risk of significant harm all options are open to the court – the search is for the option most consistent with the child’s welfare, subject only to the fact that the court must not interfere with family life if it isn’t necessary or if some lesser interference would still meet the child’s needs.

Another statistic that Foges has missed is the one showing that the average duration of care cases is now 28 weeks (also in the same statistical release she relies upon). That 28 weeks has been achieved because deadlines are set for the “shaking out” of all the cousins, and assessments of them are progressed concurrently with a plan for adoption so that a decision can be made as to which of the various options is best likely to meet a child’s long term holistic needs. Some would argue that the insistence on speed increases the risk that some children may be going to adoption when it may not be necessary because it is deemed “too late” for family members to be assessed or there isn’t time to allow a parent to demonstrate sufficient change. Some would argue that the well intentioned rush to a decision may mean some children are placed in unsafe or “wobbly” parental or kinship placements because of rushed assessments. Either way, those who wanted quicker adoption have got what they asked for – whilst the Family Court system undoubtedly needed to become more efficient and less sluggish, the quid pro quo for the ever increasing focus on the clock may be an increased risk of getting the wrong answer in some cases. It’s in that context that one should approach what Foges says about family placements.

The level of breakdown of kinship placements is a legitimate topic for debate. But Foges is bordering on social engineering when she says that :

There is another uncomfortable truth about family placements, which is that some families have bad news written right the way through them. “Man hands on misery to man”, as Larkin said, and the same can go for dysfunctional parenting.

With that attitude, why would one “waste” funds on supporting failing parents to improve themselves?

And, as we have seen so many times before, this proponent of adoption has segued into adoption as an end in itself – more adoption is a GOOD THING :

But the continuing fall in adoptions suggests the movement to keep families together at all costs has gone too far. The government urgently needs to restore balance to the system and get more children into stable, loving adoptive homes.

Those interested in an alternative approach to the issue of struggling families and child protection may care to listen to the piece by Sanchia Berg on Radio 4 Today this morning, which you can catch up on here and may wish to read the recent judgment of HHJ Wildblood QC in A Local Authority v The Mother & Anor [2017] EWFC B59 (13 September 2017) about the waste of resources and unnecessary repetition of human misery that is caused by our failure to support “failing” parents, along with the BBC coverage last week about the struggles that even adopted children have in their happily ever after homes.

Feature pic courtesy of Pelle Sten on flickr – thanks! (Creative Commons licence)

“Fast is fine, but accuracy is final.” – Wyatt Earp.

It would be nice to think that the only children to have been adopted were the ones who were in circumstances that made adoption the best solution for the child, and that contact with natural family was not severed ‘unless the circumstances are exceptional and there is no other realistic option’. But that is not happening – To give an example, [edited] Realistically [edited] there are some cases that you read and think, surely the adopters don’t know the truth, they can’t, who would set themselves up to be rejected when the child learns the truth? And I talk about rejection because…… (and I think it’s a very basic human test the courts fail to apply) I would be white hot with rage if I was adopted and I found out somebody had done that to my Mother. How many professionals have worked on cases whereby they would feel the same had somebody done that to their own Mother?

Another phrase comes to mind ‘if you can’t say why you did it, don’t do it’. So, if you cannot reasonably explain to a child why they are adopted, without the use of ‘abstract concepts’ then don’t have them adopted. If you cannot explain why a child was refused contact with the natural parents ‘don’t refuse contact’, etc. God bless those children who were adopted for ‘future risk of emotional harm’ whose parents couldn’t take the pain and ended their own lives………. emotional harm? I’d say that will be quite emotionally harming.

NB. This was my original thought when reading your article, but I got sidetracked.

If the number of children being adopted for abuse or (willing as opposed to poverty) neglect. Then I would expect a round of applause across the board, because it is the right thing to do, and in those circumstances, perhaps the ss should be making more of an effort to identify and assess family members earlier on in proceedings.

Thanks so much for this balanced piece. I’ve recently being made aware of this project http://www.coventry.ac.uk/CWIP

It is worth watching the U-tube video associated with it because it is very thought provoking from the point of Adoption ( and disability my own area of interest)

It identifies that in a poor neighbourhood within a wealthy borough there are a lot more children on child protection plans than in a poor neighbourhood in a poor borough but surely ‘abuse is abuse’ and ‘neglect is neglect’ so how to explain this ?

Maybe these concepts are actually relative in which case it is hard not to see an element of social engineering in adoption e.g. we want all our children to be like the children of wealthy parents, in nice houses etc and with no need to ‘bother’ statutory services ( because actually all we care about is the bill we need to ‘pick up’ in providing services ) Its important not to feed this nasty narrative about parents with difficulties parenting as in some way ‘worthless’ so thank you.

In one year alone, there were more adoptions from the Whitehawk estate in Brighton (poor estate in a wealthy city) than there were in the entire city of London. I cannot remember if that was 2009, 2010, or 2011. But Brighton and Hove in the field of adoption are the famed – child removed for ‘psychobabble’ council. The one where the adopters wouldn’t hand the child back when told to, who then agreed that she should have contact with her siblings, but then moved abroad so she couldn’t. Apparently these sorts of people are better parents for the children (on what planet I don’t know), people who are (selfishly) quite happy for babies to be removed for future risk, and they then go on to deny the natural parents any contact at all. Surely this ‘better parents’ thing has to be about money, because it’s not about their humanity. That little girl who was ordered to be returned to her parents………… how on earth they could not return her, but go on to take her abroad away from her siblings. What utterly ghastly people. Better? BETTER?

I also suspect that many adoptive parents are so desperate for children they do not want to ask too many questions about who is ‘supplying’ the child, until they learn the hard way what it feels like to be at the receiving end of trying to get help for a child with extreme difficulties and finding there is no-one to turn to. I actually have a lot of sympathy and respect for them and their children just think many have been taken advantage of.

Adopters who don’t question the current controversy surrounding the ‘future risk’ adoptions are just like people who want pedigree puppies that are cheap. They are quite happy to let the breeder bring a box of puppies to them, rather than go to the breeder, because they’d have to see the Mother, and most likely she’s on her 7th litter with a gut that drags on the floor, sleeping on newspaper. If they don’t see her first, they can buy a puppy with a clean conscience right?

I am disappointed that you so heavily edited my comment Transparency project. I gave a factual account of a case, without even identifying the gender of the child involved. No hint of the LA involved, and quite frankly, it would be impossible to identify said child from what I wrote. The case is shocking though, so I am not surprised you don’t want it on here. When, not if, but when, the pendulum swings back to family preservation, and the current scandal of repeated ‘expert witness’ assessments (until one gives ss something to run with) and adoption for vague prophecies of future risk does finally make huge waves in the mainstream media. The three cases I mentioned would be the sort of cases making the headlines, and you know it! NB, the awfully slow moderation really stifles debate at the ‘not so transparent after all project’.

We rarely edit posts Anon-a-mouse but it was necessary to edit this one for legal reasons. We don’t edit because we don’t like or agree with what is said.

As for moderation speed – we are a small charity run mainly by volunteers. We moderate as quickly as we can given that people are giving up their free time to run the site.

The family court system is bias, name a case where the father is the named perpetrator, NEVER, obviously it is always the mother, the father can get on with his life fathering as many children he wants to, the mother, the end to mother-hood.

The mother is always searched out by adopted children knowing her childless life, and no further siblings to inherit.

UK, you are right (unfortunately) it would appear to me and others that once a child is removed, that said Mother will be the governments broodmare from then on in. I was shocked after having spoken to a ‘professional’ that parents involved in proceedings are handed a leaflet after their child is adopted that says the equivalent of, if you need support, give us a ring. SHOCKING. These people remove children and hand the parents a leaflet, which asks them to call the very people who removed the child! – maybe they are hoping that the parents wont come crawling for support and they can save a few pennies. Support which one Father told me, was 6 counselling sessions maximum. DISGUSTING. I looked up post adoption support in my local area, and I kid you not, at the top of that webpage, was their ‘make a difference to a child’s life, and adopt!’ advertisement – That to me would be more insulting than if somebody hocked back and spat in my face. There should be a statutory duty to support these parents until they are free and clear of the problems that the ss accused them of having in the first place. This support should not be provided by the LA either, a parent should be free to choose their therapist, and the LA should foot the bill. After all, they don’t want to keep seeing the same woman in proceedings time after time (or at least this is what they claim). It’s not like it cannot be afforded given that the profit that family courts make was recently published, and it’s a rather large pot. It seems clear to me that they are quite happy to remove a woman’s first born on vague prophecies of future risk, and put a marker on her file – ‘If this one falls pregnant again, that’s one more towards our published targets’. It is just not good enough. But hey why spend on average half a million on hunting down a new Mother for the ritual disembabyment for vague prophecies treatment, when you can use the same woman over and over and over, using the fact that you removed her previous child against her. NB. ss said a while back that if women kept leaving the jurisdiction before birth so that they may be assessed elsewhere, that they would have to start lying to women by saying that they weren’t intervening whilst making arrangements for the baby snatch. They have put that plan into action already!

what is the huge profit made by family courts that you are referring to anon a mouse? are you referring to some published figures or report somewhere? can you provide a link?

This is what I am referring to Lucy,

http://www.marilynstowe.co.uk/2017/07/20/government-makes-more-than-100-million-in-profit-from-the-court-system/

Either way, whether from the courts or the LA, money needs to be found to support natural parents whose children have been removed. Even more so the ones who have lost children to ‘future risk’. One would expect that the parents are offered something better than one Father told me he got – 6 counselling sessions. Ugh, that’s an insult given that the LA used three different psychologists during proceedings (dutch auction of expert witness’, or more accurately, ‘hired guns’). They can find the money for repeat expert witness’ until one creates a juicy report, but not for aftercare?! Beggars belief.

Oh right. That doesn’t actually evidence your assertion that “It’s not like it cannot be afforded given that the profit that family courts make was recently published, and it’s a rather large pot.” It’s about the amount of fee income across the entire courts system (only a minority of which is family). It doesn’t tell you anything about the costs of running the family justice system or therefore about any “profit”. I don’t disagree with your suggestion that the government more widely should make funds available to better support parents – even if for no other reason than for longer term costs savings – but its not a job for HMCTS, nor is it one that the article you cite demonstrates is within their budget.

‘The amount of money generated by HM Courts and Tribunals Service (HMCTS) exceeded the amount spent on the system by just under £102 million new figures reveal’. I trust Marilyn Stowe as an accurate source of information. The rest of the article details which particular courts generated the most income, and which generated the most loss. It also gives the total sum of what was spent on the system. To me, having worked in business, total income, minus total expenditure, the sum you are left with is what I call profit. I would like to add that I did also say, whether the money is found from the courts or the LA, money needs to be found to support natural parents. It isn’t something that the court is responsible for, maybe if it were, it would be in place already. Perhaps a judge giving an order that a parent should be supported, until that support is no longer needed, would be a great reminder to the social work vocation that it is utterly inhumane to remove a child (I am referencing ‘future risk’ removals here) and leave a natural parent to just ‘deal with it’ by themselves, which I have seen happen often enough. By the way, if I had a moment away from my current work, I could probably write up a plan for psychological support for natural parents support (nationwide scale) that would be a very small fraction (P.A) of £102 million. I am glad that we agree that funding should be made available though.