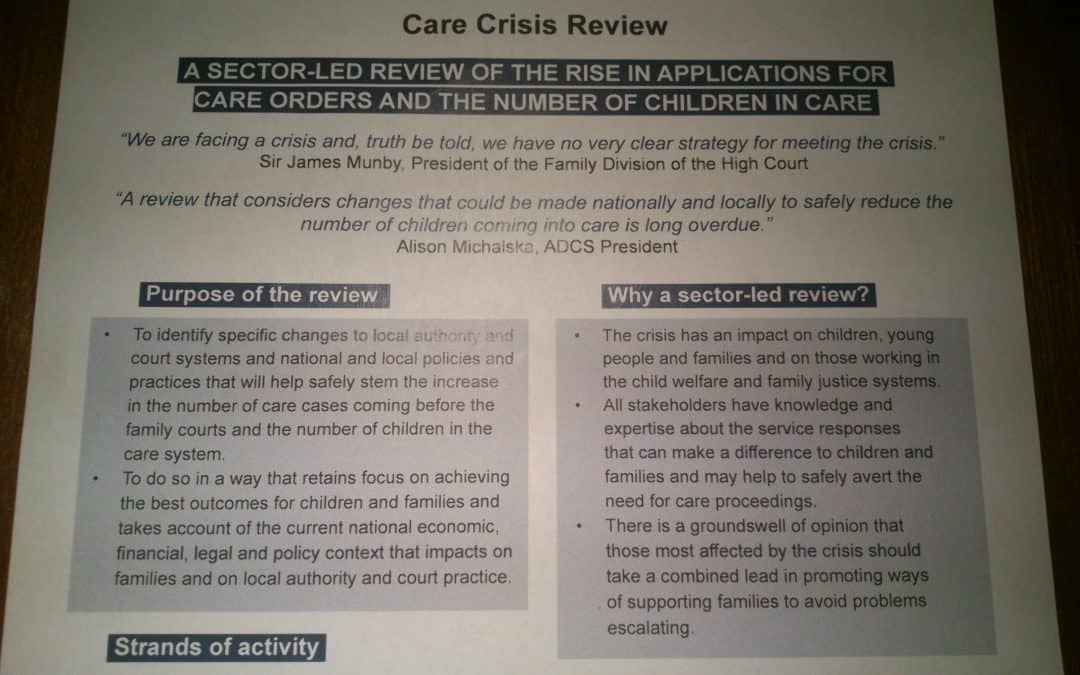

On 10 January, I attended a round table meeting arranged in Wales about the Care Crisis Review, which is a short-term enquiry funded by the Nuffield Foundation into the reasons for the rise in numbers of children in care and going through the courts. (A similar meeting was being held in England on 17 January.) As the chair of the review, Nigel Richardson, explained in his introduction, the review is looking for practical ideas and solutions about the number of children coming in to care – not reviewing the care system as a whole. His question for the day was:

Do we understand the nature of our response to child welfare concerns which is leading to a pattern of more children being cared for by the State, despite the fact that law and policy is clear that their family is the preferred place for children to grow up in?

Get involved

As the Review webpage explains, there are ways for everyone who has an interest in this topic to get involved.

The plan for the Review, other than the round table meetings, is:

- Stakeholder groups on causes, recommendations, implementation and action: February to June 2018.

- Call for information and a survey on promising approaches: November 2017 – June 2018

- Consultations with children and young people, parents and kinship carers: February and March 2018

- Engagement with directors of social services, the voluntary sector, professional associations and politicians: November 2017 to May 2018.

- Events on options for change: March and April 2018.

The Wales round table

This first meeting, of five hours’ duration, was facilitated by Family Rights Group and hosted by Cardiff University School of Social Sciences. It was very well attended, with representatives from local authorities, Cafcass Cymru, third sector, members of the judiciary, civil servants from Welsh Government, lawyers and academics. Caroline Thomas, a researcher of many years’ experience, presented a summary of research evidence. This was organised into four overlapping categories: economic; legislative and policy frameworks; professional practices; and the nature of cases, but she explained that these overlapped and their relative impact was hard to dis-entangle.

In a nutshell, the number of children in care in England and Wales has doubled over the last 20 years. Although delegates put forward some ideas for underlying reasons, a phenomenon new to me (and I think to most people present) was that, despite peaks (the Baby P effect, for example) the rate, in Wales at least, has been a steady increase since the Children Act 1989 (with its non-intervention principles) was implemented in 1991. The interval during the Blair/Brown years from 1997-2010, when government invested heavily in reducing child poverty and brought in supportive programmes like Sure Start, and there was a break from Conservative rule, does not seem to have made any dent in the relentless pattern of more children going in to care. (The implication was that this is the same in England, but we only saw Wales statistics.)

Two major problems that emerged in the Wales context was, first, the perception amongst local authorities that they would be criticised in court for using voluntary accommodation to look after a child before issuing proceedings. This is the section 20 Children Act provision which is replicated in section 76 Social Services and Well-being (Wales) Act 2014. An effect of this was that s 76 arrangements for young teenagers (under 16s) that had been working well were now being disrupted because social workers were fearful that if something did worsen and a s 31 application was necessary in the future, they would be criticised in court. This perception had arisen since the case of Re N published in November 2015, in which the President of the Family Division had been critical of the way s 20 had been used in that case. Re N, however involved very young children and, in hindsight, it was clear that s 20 had been used inappropriately and for too long before proceedings were issued. However, the message that has got through is that s 20 (s 76) is to be avoided and even curtailed, where it is working.

We wrote about Family Rights Group’s work to address this issue here.

An associated effect of Re N in Wales was that local authorities could be uncertain as to how long they should work with a family, trying to support them with s 76.

As Judith Masson has pointed out in this Family Law Week column, s 20 was designed as a support service, although some judges now seem to interpret it as delaying tactic.

Second, there were differing views amongst some of those present as to the extent of support kinship (family and friends) carers were being offered so as to avoid a child becoming looked after. Research across England and Wales indicates that support tends to be linked to legal status rather than need, with looked after children, and their carers, being most likely to receive support, since this is a statutory requirement. Support for other forms of arrangement, which is dependent on the discretion of the local authority, is much more patchy. However, some people at the round table from Wales believe that local authorities fulfilled their responsibilities to support kinship carers (where suitable) outside the looked-after system because this was always the preferred option to being in care.

I found these discussions enlightening and constructive and feel optimistic that the Review will be able to identify areas where tensions and miscommunication might be resolved.

The surveys are now here –

https://www.surveymonkey.co.uk/r/care-crisis-review-survey-for-practitioners

https://www.surveymonkey.co.uk/r/care-crisis-review-survey-for-family-members

Deadline for responses is 11 February.