A few months ago, Paul Magrath wrote a post on the figures behind the Daily Telegraph’s headline “financial abuse rockets as more powers of attorney challenged by courts”, showing that the rocket turned out to be a very small damp squib.

The subject of that post came up again last week, when we looked at updated statistics for financial abuse by attorneys in our first and second posts on the recent debate about the potential scale of abuse of lasting powers of attorney. This debate was prompted by remarks made by retired Senior Judge of the Court of Protection, Denzil Lush, in an interview on the BBC Radio 4 Today programme on 15 August 2017. Once again, our conclusion was that the actual reported statistical scale of financial abuse was much smaller than some of the speculation and headlines might suggest.

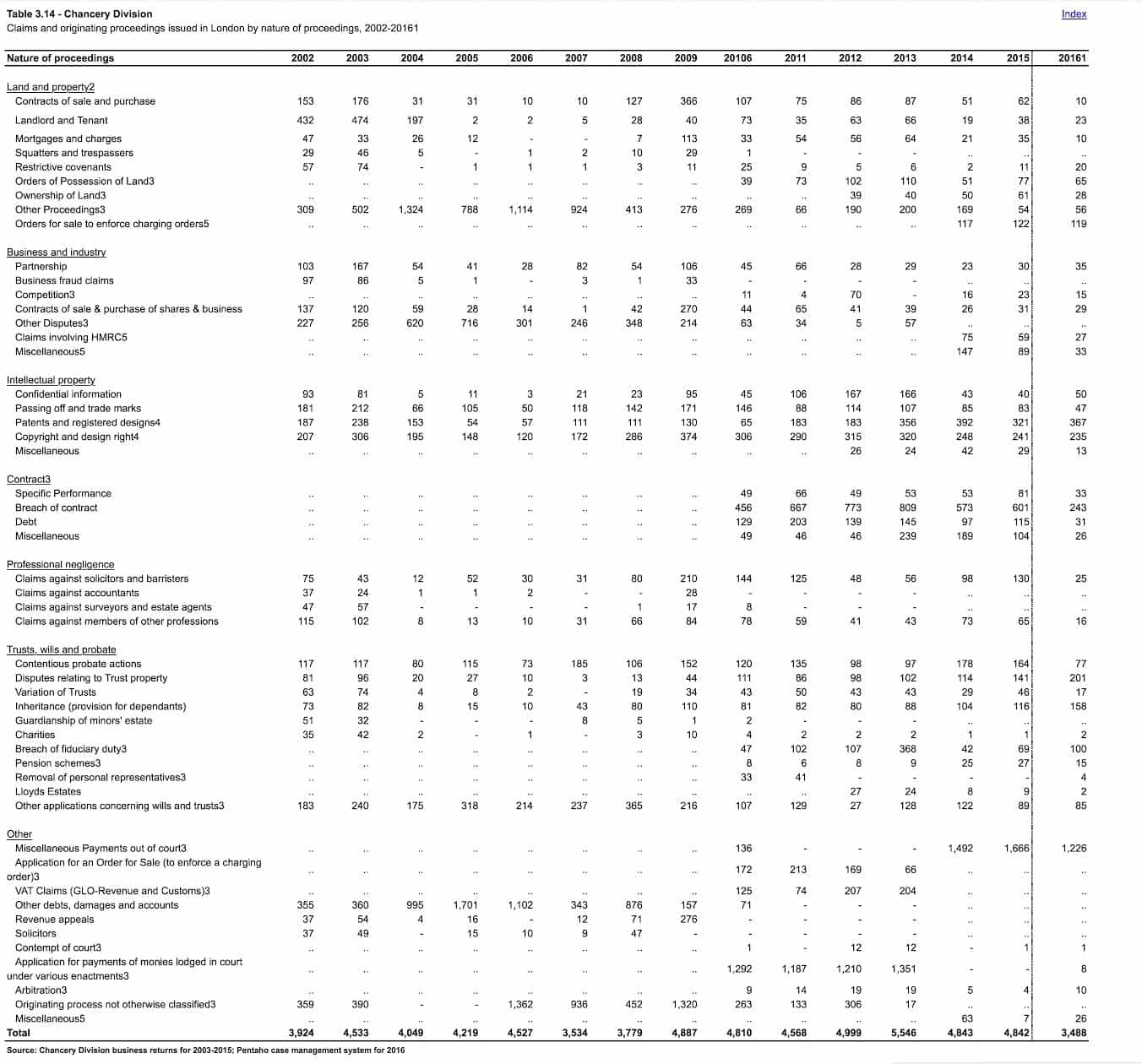

Dramatic statistics have also recently made a headline for the Financial Times (£) on 23 August 2017, which claimed “Family disputes over inheritance surge 36% in 2016”. The story went on to say that the number of claims under the Inheritance (Provision for Family and Dependants) Act 1975 brought in the High Court

reached 158 in 2016, a 36 per cent increase on 2015, when there were 116 High Court claims. The number of claims has reached 10 times what it was in 2005, when just 15 Inheritance Act cases were heard in the High Court

The Inheritance (Provision for Family and Dependants) Act 1975 is an important Act which entitles certain categories of claimants to bring post-death claims for reasonable financial provision to be made for them out of the estate of someone who has died. The categories are spouses, civil partners, former spouses and former civil partners, cohabitants subject to a qualifying period of cohabitation for two years up to the death, children whether under 18 or adult, people treated as a “child of the family”, and anyone who was being maintained by the person who died immediately before their death. There are sometimes disputes about whether or not a person is eligible, particularly cohabitants and people who were being maintained. The court has to decide whether the will or the intestacy of the person who has died has failed to make reasonable provision for the claimant, and if so, whether, and what, reasonable provision should be ordered. This is a discretionary decision taking into account a very wide range of factors, some of them specific to different types of claimants and set out in the Act.

The source of the data quoted by the Financial Times is the most recent Civil Justice Statistics Quarterly published on the Ministry of Justice website, and specifically table 3.14 (below) which is a breakdown of claims and originating proceedings issued in London between 2002 and 2016 in the Chancery Division of the High Court. It shows the figures quoted by the Financial Times. The complete dataset is more revealing, as it shows figures very similar to those in 2012-3 for 2002-3, followed by a sharp fall in 2004, rising again in 2008 and 2009 and reaching 110 in 2010.

Importantly, what this dataset does not show is

- The number of issued cases which proceeded to a full trial hearing. The Financial Times says that in 2005 “just 15 Inheritance Act cases were heard in the High Court”, but it certainly doesn’t follow from the fact that 15 were issued, that 15 were heard. The majority of civil claims end in a negotiated compromise, and Inheritance Act claims are no exception.

- The number of claims issued or heard in the Family Division of the High Court in London, which has concurrent jurisdiction with the Chancery Division over claims under the Inheritance Act.

- The number of claims issued or heard in any of the District Registries of either division of the High Court in a number of other cities outside London in England and Wales.

- The number of claims issued or heard in any county court. There is no financial limit on the county court’s jurisdiction under the Inheritance Act. Taking the regional jurisdiction of the High Court and the county courts together means that it is possible to issue an Inheritance Act claim in any town or city in England and Wales where there is a civil court.

I haven’t been able to find published datasets for these further issued claims (the Family Division figures are not shown in the same table as the other High Court civil justice statistics) but they would certainly add very significantly to the number of claims issued every year. Also, even a complete set of court claims issued statistics could never give a true picture of the incidence or progress of 1975 Act claims, because a very large number of prospective claims are compromised – often at mediation – without issuing proceedings at all. Often, a claim is issued in order to ensure that it is made within the short limitation period for claims under the Inheritance Act, but followed immediately by an agreement not to take active steps in the proceedings and pursue a negotiated compromise instead. The limitation period is only six months from the date of probate, in order not to hold up the distribution of estates for too long, although the courts have discretion to extend the time limit beyond the expiry of the statutory six months, if they feel it’s justified. Many solicitors prefer to ensure that they have at least filed their client’s claim within the primary limitation period instead of relying on a standstill agreement negotiated with the defendants to the claim as an alternative.

Taking the Financial Times figure alone i.e. the claims issued in the Chancery Division of the High Court, means taking what is on any view a very small figure, to which any change may appear statistically dramatic, simply because the figure is so small. The figures need to be put in context. 525,048 deaths were registered in England and Wales in 2016 (Source: Office for National Statistics). 158 claims represents approximately 0.03% of all deaths in the population. A more useful starting point than total annual population mortality may be the statistics for estates in which a grant of representation is issued, and out of those, the statistics for estates liable to inheritance tax (“IHT”). This is a rough way of identifying estates of significant value, against which claims are more likely to be made. It is only a rough way, because even valuable estates may pass entirely by survivorship to a spouse or civil partner, without a need for a grant of representation, or giving rise to IHT. However, it reduces the starting figure dramatically, and is also a meaningful starting figure, as realistically no Inheritance Act claim can be commenced unless there is a grant of representation in the estate and properly appointed personal representatives to put any order made or agreed on the claim into effect. In 2014-5, the most recent year for which statistics were published by HMRC (on 28 July 2017), 284,756 estates issued a grant of representation, and this accounted for c48% of all deaths in that year. Of those estates, 23,250 were liable to IHT. Even taking the smaller figure of 23,250 estates, 158 claims account for a mere c 0.7% of all IHT-liable estates. This must be virtually, if not completely, statistically meaningless, and any change in the percentage year on year, likewise microscopic. Even if the number of issued claims was multiplied by a factor of 10 to 1,580 to take a roughly estimated account of all those not issued in the Chancery Division in London, and those which are compromised without issuing court proceedings at all, it would still account for less than 10% of all estates liable to IHT, which is in itself only a fraction of estates for which a grant of representation is taken out. 1,580 claims would not even account for as much of 1% of the 284,756 estates for which a grant of probate or letters of administration was issued, and the recorded figure of 158 would not even amount to 0.1% of 284,756.

With a statistical context of this Lilliputian size, I think that any analysis of statistical trends which identifies a “surge” must be taken with a large pinch of salt. The Financial Times sub-heading reads “High-profile court ruling in 2015 contributed to rise in claims, say experts”. This is a reference to the July 2015 decision of the Court of Appeal in the case of Ilott v Mitson – a very long-drawn out case about reasonable provision for an adult child, Heather Ilott, who was estranged from her late mother, and whose mother’s will disinherited her daughter in favour of some charities. The July 2015 decision of the Court of Appeal was generous in ordering provision for Heather Ilott, although that generosity was largely reversed by the final decision in the case made by the Supreme Court in March 2017 and reported at [2017] UKSC 17. The Financial Times says

The [Court of Appeal] ruling has been seen by many as a source of encouragement to adult children who have been left out of a will or not provided for to any great extent to dispute their parent’s decision.

It is possible that the 2015 decision of the Court of Appeal in Ilott v Mitson prompted a rise in adult children’s claims under the Inheritance Act in 2016, but that cannot be a long-term trend in view of the substance of the Supreme Court’s decision, which is widely regarded as relatively discouraging to such claims, and it is surprising that the article does not even mention the existence of the Supreme Court’s judgment in its analysis.

My own view is that the true picture is more complex, and that the statistics are not meaningfully revealing year-on-year. It is true, as the article suggests, that greater complexity of family and long term financial dependency relationships, together with a rise in asset values, particularly the property assets of the currently elderly, are factors which are likely to have underpinned an increasing number of claims. But the effect of these factors is attributable to a much longer term view than simply year-on-year in the past couple of years. In my own professional lifetime since 1991, the categories of eligible claimants have notably increased through legislative change: since 1 January 1996 cohabitants have been eligible to claim as cohabitants, without having to prove financial dependency; since 5 December 2005 civil partners have been eligible to claim in exactly in the same way as surviving spouses, and further changes were made to the definition of “child of the family” and other aspects of the Act in 2014. Another longer-term factor which may have driven a rise in claims is the increasing use and availability for this type of claim since 1998 of litigation funding arrangements such as conditional fee agreements. Many Inheritance Act claimants rely on these and would find it difficult or impossible to bring claims without them.

The Financial Times article also mentions that intestacy laws

often fail to reflect modern living arrangements, such as cohabitation outside marriage or a civil partnership.

This is simply wrong, so far as civil partnership is concerned, as civil partners have the same intestacy rights as spouses. It also fails to mention that both spouses and civil partners have benefited from changes in 2014 which increase their entitlement on intestacy, and in my view these changes are likely to reduce rather than increase the incidence of spouse/civil partner Inheritance Act claims against many estates.

So all in all, neither the statistics nor the accompanying analysis really tell a full story about trends in claims under the Inheritance Act, still less about the varieties and realities of outcome for such claims. Headline writers should control their surges and reach for a pinch of salt instead.

Featured image – Abacus by Jenny Downing via Flickr – thanks

It is my experience that claims are very definitely increasing under the 1975 act and often by grown up children who are made aware that the cost of defending such claims for small estates, perhaps for example with a house and no liquid funds, is prohibitive. The choice is large legal fees or ‘make an offer’ for £25,000 to £50,000 to make the claim go away.

Few of these small estates will take the matter to the courts.

Sadly, there seems to be more and more abuse of the 1975 Act.