‘A good law gone bad’ is how the Hague Convention on International Abduction was described in a session organised by the Filia Hague Mothers project at an international feminist conference held in Cardiff over the weekend. The Convention was drafted in 1980 and implemented in the UK in 1985. More than 100 countries have now signed up to it. Its primary purpose was to help parents whose ex-partners had seized their children and taken them abroad to another jurisdiction, or who had gone abroad by agreement but then refused to return the children home. It was designed to bring children back into their own jurisdiction swiftly, where any outstanding legal issues over residence and the child’s best interests could be dealt with in the relevant court. Typically, a parent who removed a child was envisaged as a father who had the resources to travel abroad, leaving the primary care giver, the mother, needing legal support.

However, by the 1990s, it became clear that the Convention has developed into a mechanism whereby about three quarters of applications are made by fathers, and in many cases where their ex-partners have fled an abusive situation with their children. These mothers are not fleeing to some far-flung country on a whim, but usually returning to their own home country, where they are likely to have family and community support. However, under the Convention, they are faced with the prospect of returning to the dangerous situation they tried to escape, with no guarantee of due process when they arrive, branded as abductors. Children’s best interests are assumed to be served by making them return.

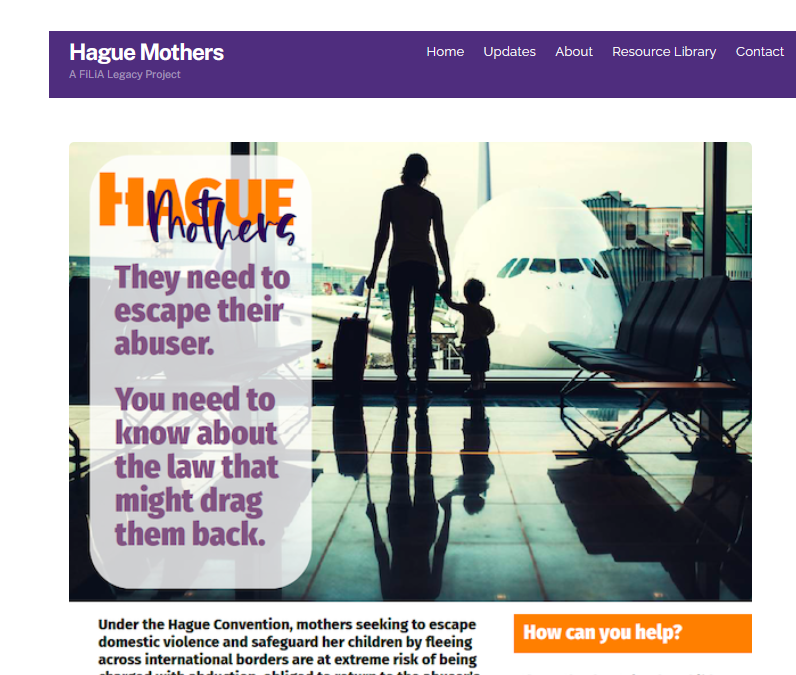

Awareness of this dilemma, affecting many families, led to the Hague Mothers project being set up by Ruth Dineen and adopted as a Filia Legacy project last year. The aims of the project are to:

- Amplify the voices of the women who are further abused as a result of decisions made under the Convention to return their children;

- Raise awareness of the issues;

- Work with lawyers, domestic violence and children’s rights experts, women’s groups, and Hague victims, to put right the injustices perpetuated by the Convention.

On Sunday, the concert hall in Cardiff was packed with supporters, and several Hague mothers themselves, to hear Ruth introduce three inspiring speakers: Kim Fawcett from the UK; Gina Masterton from Australia, and Sudha Shetty from the USA. Kim, a teaching fellow in law at Durham University explained the original rationale in 1980 of gathering the parties and children to one jurisdiction to settle the legal issues but pointed out that there was nothing that would protect those who were compelled to return to countries where they were at risk of harm. In this age of virtual international meetings and hearings, she argued, this step of getting people physically in the same place was no longer necessary. Gina, a barrister and researcher in Queensland, talked about the lack of knowledge about the implications of the Convention amongst judges and lawyers in Australia. Sudha got the audience very excited with her account of the achievements of the Hague Domestic Violence Project at Berkeley University, California.

The session came to an end with a tribute to Narkis Golan, a Hague mother who had succeeded earlier this year in the US Supreme Court in preventing her 7 year old son having to return to a violent environment in Italy. Narkis had died just a few days earlier. A very moving statement she had prepared about her experience and her hopes for the future was read out by a friend of hers, who had travelled to the conference from the USA.

Although families across borders still have better prospects of achieving justice where the countries are Hague menbers than not, it is clear that Convention itself urgently needs review.

A legal overview of the current Convention process is on the Hague Mothers website, which has a newsletter and a growing bank of resources for parents and professionals.