This is a guest post by Jo Edwards, Partner and Head of Family, Forsters LLP. Jo tweets as @MissJoEdwards.

The headline in last Wednesday’s Daily Mail, a week to the day since the new no fault divorce process was introduced in England and Wales, was as predictable as it was tiresome – “Divorces surge by almost 50% as ‘no fault’ law comes in, fuelling fears the rule change has made marriage splits easier”. Even from the tranquility of my holiday apartment balcony in Lisbon, sipping on a Ginjinha, I felt my heckles rising.

I had spent “No Fault Divorce” day itself doing media rounds on Resolution’s behalf, telling as many journalists who would listen what a positive change this was for families and the arduous journey we had had getting to this point. I stressed that practitioners fully expected that over the next year or two, divorce numbers would increase but that this was normal, had been seen in other countries and was (I repeat) NOT A CAUSE FOR ALARM. I didn’t expect, however, to be having to contend with alarmist articles about this phenomenon quite so early on.

Before looking at the detail of the article, let’s get some context by looking at what we know about divorce rates in England and Wales, which in fact have long been in decline. The ONS statistics published in February 2022 showed that in 2020 there were 103,592 divorces granted, a reduction of 4.5% year on year, possibly due in part to the impact of Covid-19 and the temporary suspension of operations by some courts for a time. The average duration of marriage at divorce was 11.9 years for opposite sex couples, a decrease from 12.4 years in 2019. The clever folk at the Marriage Foundation, who do a much deeper dive into such things, point out that while there was an 18% rise in divorces the year before, in 2019, that was a statistical anomaly reflecting the unwinding of delays in the legal system the year prior; and that divorce rates remain at or close to the lowest levels in 50 years. They reason that as social pressure to marry has dissipated and more and more people cohabit, those who do marry today are serious about it and therefore more committed. None of those social mores change as a result of no fault divorce.

So what are the charges laid in the Daily Mail article, also picked up in the Independent? As I read on, I realised that the case for the prosecution had three main planks.

1. That there had been a massive increase in divorce applications

(see how easily we have moved into the new, more modern parlance? – in the first week of no fault divorce)

Well, durr.

Despite certain quarters of the media jumping on tales from some family lawyers in late March of there being a positive clamour for people to apportion blame and brisk business in such petitions, the majority of the lawyers I spoke to said that they had clients lined up waiting to issue their no fault applications (individually or jointly) from 6 April when no fault divorce came in. That was my own experience, as a solicitor and especially as a mediator.

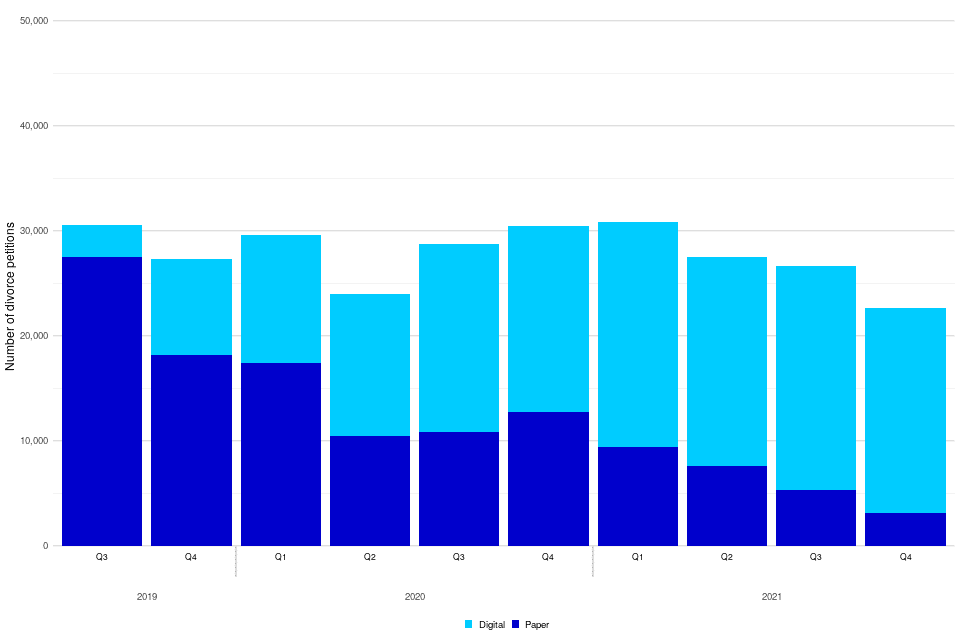

The more scientific evidence of this came in the shape of the Family Court Statistics Quarterly – still my guilty pleasure – for October to December 2021, published on 31 March 2022. They revealed that divorce petitions were down by 26% in Q4 2021 compared to a year prior (22,683 petitions, compared to 28,672 in Q4 2020, itself back to pre-pandemic levels following a dip in Q2 2020 with the onset of Covid restrictions) –

It will also be evident from the table above that whilst Q1 2021 saw the highest number of divorce petitions in 18 months, there was then an ongoing decline in the number of petitions being issued for each successive quarter in 2021. This is consistent with people wanting to await the coming into force of no fault divorce. The Divorce, Dissolution and Separation Act got Royal Assent in June 2020; a consultation was launched on the draft changes to the Family Procedure Rules in December 2020 and for a time it was hoped that we may have no fault divorce from October 2021, though eventually the need to work on the portal pushed that aspiration back by 6 months. All told, however, lawyers have had a lot of notice of the change, and the public seem to have got the memo too.

Thus it should come as no surprise that in the very first week of no fault divorce, there would be a surge in the number of applications. There is clearly pent up demand, as the 2021 statistics suggest. It is also statistically right that if around 3,000 couples issued a divorce application in the week 6-12 April, that would be around 50% more than in an average week – very broadly speaking, around 25,000 divorce petitions are issued per quarter, or around 2,000 per week.

So far, so good.

2. That the increase in divorce applications was due to the new law and will continue to spiral upwards

The article itself, in fairness, says simply that “The new divorce law…was opposed by some Conservative backbenchers who feared it would lead to ‘an immediate spike in divorce rates'”. That probably conflates two issues, which I shall endeavour to unpick.

First, most MPs – like the rest of us – accepted that there would be an immediate (but short-lived) spike in the number of divorce applications after the coming into force of no fault divorce. Indeed, one needs only look to Liz Trinder’s Finding Fault research both to back up this proposition, and to reassure us that this will be a temporary phenomenon :

“There is now a large and impressive body of research…on the relationship between divorce law and divorce rates, particularly in relation to the impact of the introduction of no-fault divorce. Some early studies from the US and Europe did suggest that divorce law reform, especially no-fault and unilateral divorce, might raise divorce rates. However, there are now multiple studies, especially more recent studies, finding no effects or only temporary effects. Indeed, those earlier studies have been subject to serious methodological criticisms…

…Looking at the research as a whole, there is little consensus that no-fault or unilateral divorce has had any clear impact at all on the propensity to divorce, though it is common to find short-term blips in response to policy and legislative changes. A classic example of a short-term blip occurred following the Family Law (Scotland) Act 2006. Until 2006 Scottish divorce law was almost identical to that of England & Wales, with the same formulation of a single ground for divorce – irretrievable breakdown of the marriage – evidenced by one of five Facts. The 2006 Act reduced the separation periods from two years to one where there was consent and from five to two years otherwise. The rarely-used ‘desertion’ Fact was removed entirely. The result was a classic but short-lived mini-spike in the numbers of Scottish divorces immediately after the implementation of the 2006 reforms. Within two years…the numbers of divorces reverted to the previous level, and have continued on a slight downward trend.”

So it’s fair to say that the increase in divorce applications in that one week period most likely was due to the new no fault process (though also in the mix were the fact that effectively, no new digital divorce applications could be accepted between 4pm on 31 March and 10am on 6 April, and that there were some IT issues the week prior, both of which may have further driven up demand last week).

Second, some MPs opposed the Bill during its passage through Parliament as they feared a longer term, sustained increase in divorce rates as a result of a no fault system.

It seems highly unlikely, based on the passage above from Finding Fault and other international experience, that the move to a no fault system will lead to a sustained increase in the number of divorces. Yet that is the issue that some Conservative backbenchers voiced as being the reason for their concern behind a move to no fault divorce. A dozen Tory MPs voted against the Bill at first reading stage in the House of Commons in June 2020, saying that the plans risked “undermining the commitment of marriage” during a time of other marital pressures due to the coronavirus lockdown – “This law sends a destabilising and deeply insensitive signal which will be amplified by these intensely troubled times and it should be dropped now,” they said in a letter to The Telegraph at the time.

The reality, as we all know as practitioners, is that people rarely make the difficult decision to divorce lightly, and they do so in ignorance of what the law is. In other words, they don’t decide to divorce based on an intimate knowledge of the state of the law; they make decisions with the heart, not the head. I wrote about my own experience of people’s behaviour in the Guardian in 2018 :

“In my practice, I see first-hand the damage that a fault-based system causes to families. Few people take lightly the decision to end their marriage; they think about it long and hard, invariably having attended counselling. They are shocked to learn that unless they have been separated for at least two years, one of them will need to accuse the other of being at fault to end their marriage. That is where things can begin to go awry; tempers fray when a spouse commits to paper (because the law requires them to do so) the reasons why the other is at fault for the end of the marriage, and intentions to keep things amicable go out the window. Children are the inevitable victims.“

In another piece, for Conservative Home, in 2017 I wrote about the arguments commonly cited against the introduction of no fault divorce, including the suggestion that people make decisions to divorce based on their knowledge of the law and that the law needed to disincentivise them to do so. I tried to shut down those arguments as follows :

“Of the arguments I have heard against reform, these are the most common:

1. It will lead to an increase in the divorce rate. Academics have shown that this is not the experience of countries where no-fault divorce has been introduced. Instead, the trend is a short-term increase in the divorce rate (as people wait for the new legislation) and then a return to previous levels.

2. Divorce should be hard, to disincentivise people. Really? The fact that most are ignorant of the law at present shows that this does not drive their decision-making. Second, few people treat their marriages as disposable; they reflect carefully before making a final decision. Third, is it the place of the state to keep people trapped in unhappy (sometimes abusive) marriages, unable to access financial remedies until they have proven the breakdown of the marriage?

3. We have no-fault divorce already – two years’ separation. But few people want to wait for two years’ separation, particularly where the decision to divorce is mutual. No divorce is speedy – fault-based divorces take 5-6 months even if undefended – but forcing people to stay together for two years (even then, assuming mutual consent) is paternalistic and wrong.“

The final word on this topic though must go (again) to Liz Trinder in Finding Fault, who is clear that there is no causal link between no fault divorce and long term divorce behaviour :

“Overall, we find little evidence that fault protects marriage, and that instead fault simply enables a quick exit from a marriage. We also find little evidence of the effectiveness of the various legal provisions contained in the Matrimonial Causes Act 1973 to promote reconciliation. One issue to emphasise is the crucial distinction between the relationship breakdown and the legal divorce. It is likely that the grounds for divorce may influence the timing of the divorce proceedings, but it would appear to overstate the influence of the law in people’s lives to suggest that the law might influence whether the personal relationship does or does not break down. It is in any case an unlikely argument that having to provide evidence of fault would mean that people tried harder to stay together or did not split up“.

3. That no fault divorce has made marriage splits easy…

There are two ways of looking at this.

First, and my stock, perhaps slightly defensive response to any journalist who fires this suggestion at me – it’s not about making divorce easy, it is about making it a kinder process. Removing blame doesn’t automatically mean that separating will be pain-free in every case; any separation is hard. However, by not building in a legal requirement of having to point the finger and decide who is at “fault” right at the start of the divorce process, it makes it a heck of a lot easier to start child arrangements and money discussions from a place of calm and therefore more likely that an agreement can be reached (and more likely that such discussions will be away from the court arena).

However, there’s a second viewpoint, which can be gleaned from scanning the reader comments underneath the article (my other guilty pleasure)–

- “Wasn’t the whole idea “to make it easier” or am I missing something?“

- “Why wouldn’t you want to make divorce easier for everyone involved? Including children“

- “Why is it feared that they’re easier? If you’re no longer in love with someone then it should be easy to leave?“

- “Not sure what the problem is, if people are unhappy and want a divorce then that’s a good thing, who wants to live in an unhappy unhealthy arrangement that is difficult to get out of. There is no reason to force people to be stuck in marriage, what century are we living in here? Nobody should feel like prisoner to someone else.“

I feel sure that Tini Owens, who on 6 April commented to the media that “no one should have to remain in a loveless marriage“, would say, “Hear hear!” to that.

Feature pic : DIVORCE word on card index paper, By Sinart Creative via Shutterstock

We have a small favour to ask!

The Transparency Project is a registered charity in England & Wales run largely by volunteers who also have full-time jobs. We’re working hard to secure extra funding so that we can keep making family justice clearer for all who use the court and work within it.

Our legal bloggers take time out at their own expense to attend courts and to write up hearings.

We’d be really grateful if you were able to help us by making a small one-off (or regular!) donation through our Just Giving page.

Thanks for reading!