This is a Guest Post by Anne Barlow FAcSS; Professor of Family Law and Policy and Associate Dean for Research, College of Social Sciences & International Studies at the University of Exeter. This was originally posted in the ESRC Society Now magazine as a feature and we are grateful to republish it here.

Further reading and guidance on common law marriage can be found on our Resources page by clicking here.

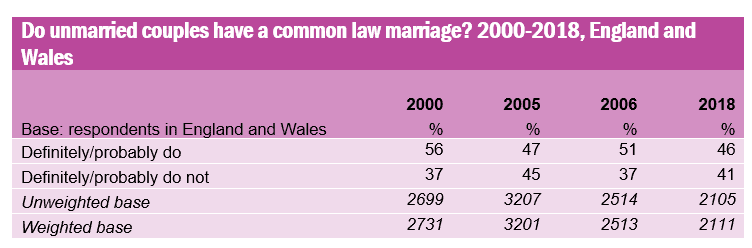

Question wording:

As far as you know, do unmarried couples who live together for some time have a ‘common law marriage’ which gives them the same legal rights as married couples?

There is no longer just one way of ‘doing’ family in modern Britain. With much greater gender equality and social acceptance of different family forms, how we organise family life and our personal relationships has changed considerably in recent times. In some ways, the law in England and Wales has kept pace with change – same-sex civil partnerships in 2004 and same-sex marriage in 2013 are shining examples of progressive legislative landmarks. Yet we have witnessed clear policy reluctance to offer legal protection to opposite-sex couples who reject marriage, despite Law Commission recommendations in 2007 and despite many other countries including Scotland, Ireland, Australia and New Zealand having reformed their cohabitation law.

Cohabiting couples are now the fastest growing type of family in the UK, more than doubling from 1.5 million families in 1996 to 3.3 million families in 2017, with 15% of dependent children living in cohabiting couple families. Successive governments have refused to legislate to recognise opposite-sex cohabitants as deserving of cohesive family law remedies when relationships break down or a partner dies.

However, recent research undertaken by the University of Exeter (funded through the University of Exeter ESRC Impact Accelerator Account) in conjunction with the National Centre for Social Research in 2018 has been used to inform Parliamentary debates in two separate Private Member’s Bills – one advocating extending civil partnerships as an option for opposite-sex (rather than exclusively for same-sex) couples and the other seeking remedies for cohabitants on relationship breakdown or death of partner. However, these offer quite different types of solutions to unmarried cohabiting couples – one involves opting into a civil partnership whilst the other offers qualifying cohabitants automatic legal rights and remedies unless they opt out. Which approach is most fitting for modern society has divided opinion in Parliament, yet do we really have to make a choice? Does the research evidence show that one option necessarily precludes the other?

Equal Civil Partnerships

On 15th March 2019, the Civil Partnerships, Marriages and Deaths (Registration Etc.) Bill 2017-2019 passed and will become law by the end of 2019. This will allow opposite-sex couples (not only same-sex couples) to enter into civil partnerships. Even though the Supreme Court had ruled in June 2018 that to preclude opposite-sex couples from registering civil partnerships was discriminatory, the government initially wanted to delay legislating to undertake a survey to gauge public opinion.

However, Tim Loughton MP, the Bill’s sponsor was able to draw on the research, assert its credibility and progress the Bill speedily to its 3rd reading and into law. As he explained:

‘I can help the Minister on that score, thanks to Professor Anne Barlow… at the University of Exeter… She has surveyed extensively using the NatCen panel survey technique, which is a probability-based online and telephone survey that robustly selects its panel to ensure that it is as nationally representative as possible…

[It] had a sample of more than 2,000, which I gather is double the amount the Government intended to survey, and which they were to take at least 10 months to do…Her survey posed the question, “How much do you agree or disagree that a man and woman should be able to form a civil partnership as an alternative to getting married?” … More than 70%—even better than the Brexit referendum—of those 2,000 people absolutely thought that civil partnerships should be made available to all.’

Whilst the introduction of civil partnerships for heterosexual couples is very welcome and will offer an alternative to couples who wish to form a legal union without entering a traditional marriage, this will only assist couples who are aware that they lack legal status.

Cohabitation and the Common Law Marriage Myth

In England and Wales, cohabitants currently have no legal status and, therefore, no automatic rights in most circumstances – especially if the relationship comes to an end. For example, if one partner dies there is no right for the other to inherit part of their estate – regardless of how long they have lived together and even if they had children together. Equally, there is no legal duty to support the partner financially should the relationship break down, even if family life had been organised so that one partner was the main earner and the other the main carer of their children.

Yet almost half of us (46%) living in England and Wales are unaware that this is the case and think that an unmarried cohabiting couple have a “common law marriage” with the same legal rights as a married couple, according to the latest British Social Attitudes Survey. This figure is largely unchanged since 2005, despite public awareness campaigns , showing how difficult it is to shift this myth.

The data also show that people living in households with children are significantly more likely to think that common law marriage exists than those in households with no children (55% vs 41%) and singles (39%). Worryingly, cohabitants (48%) are no more clued up than married people (49%).

Misperceptions like this can have very real negative implications for people’s lives and the decisions they take. Cohabitants may face financial hardship and even losing their home if the relationship breaks down. Additionally, we know that the lack of legal rights for cohabitants affects particular groups disproportionately, particularly women and children, as women remain more likely to put careers on hold while raising children and become financially dependent on their partners.

One possibility would be granting them automatic rights as put forward in Lord Marks’ Cohabitation Rights Bill, the second Private Members’ Bill debated on the 15th March, this time in the House of Lords. Its proposals are similar to those introduced in Scotland in 2006, providing a set of limited rights for cohabitants who separate, or in cases where one partner dies. Yet the Lords’ debate revealed that there are concerns that this would be inappropriate for those deliberately choosing to cohabit to avoid such legal constraints. Lord Marks, in countering these arguments, was able to use the widespread nature of the common law marriage myth to question whether this was indeed the typical rationale for such a choice. The Bill passed its second reading and now goes into committee stage.

Whilst the public as a whole need to have a better understanding of their legal status, empowering each of them to take informed decisions that suit their family’s circumstances, family law should also be able to provide a range of options for those who are ‘doing family’ in the way that suits them best, including something of an automatic safety-net which avoids one partner being able to exploit the other financially if things go wrong or one inadvertently leaving their surviving partner destitute, should they die.

Equal civil partnerships are only a partial solution for those ideologically opposed to marriage, and given the growing numbers of cohabiting couples and the widespread persistent belief in the common law marriage myth, reform should certainly not stop there.

For a discussion of the earlier research conducted in 2006-2008 see Barlow A, Burgoyne C, Clery E, Smithson J (2008). Cohabitation and the law: myths, money and the media. In Park, A, Curtice, J, Thomson, K, Phillips, M, Johnson, M (Eds.) British Social Attitudes: the 24th report, London: Sage, 29-52; Barlow A and Smithson J (2010). Legal assumptions, cohabitants’ talk and the rocky road to reform. Child and Family Law Quarterly, 22(3), 328-350.

Feature pic : Head in hands. Leo Reynolds. flickr. thanks.

quote “Whilst the introduction of civil partnerships for heterosexual couples is very welcome and will offer an alternative to couples who wish to form a legal union without entering a traditional marriage, this will only assist couples who are aware that they lack legal status.”

No it doesn’t assist “couples who are aware that they lack legal status”. They already have the option of entering a traditional marriage, if they both wish to do so. The only people it assists are those who want to form a legal union without entering a traditional marriage. This article does not explain why such couples do not consider a civil marriage inadequate for the purpose, unless it is mere preference, which need not influence public policy. If such couples say they do not like the “religious” or “ideological” aspect of marriage, they are wholly mistaken. Civil marriages have no religious or ideological connotations, and no implication that one partner is in authority over the other.

I have no objection to opposite-sex civil partnerships, only to the false statement that they actually help anybody.

quote “… [re Cohabitation Rights Bill] providing a set of limited rights for cohabitants who separate, or in cases where one partner dies. Yet the Lords’ debate revealed that there are concerns that this would be inappropriate for those deliberately choosing to cohabit to avoid such legal constraints. Lord Marks, in countering these arguments, was able to use the widespread nature of the common law marriage myth to question whether this was indeed the typical rationale for such a choice.”

What is “typical” is neither here nor there. All that matters is that some people *do* choose to cohabit in order to avoid the legal obligations of marriage, and a perfectly good and justifiable reason it is in many cases. If, as you imply, Lord Marks argued that the law should force all cohabitants to make financial commitments to one another just because many do, then his argument was stupid and can be dismissed without further consideration. If the argument is rather that all cohabitants should be forced to make financial commitments to each other just because the author thinks they should, then it should be honestly stated in those terms.

All these points are well understood both by lawyers and the public, and articles like the present one are simply being dishonest about the real issues engaged, in order to promote the author’s own political views.

Mr Loughton wanted to extend civil partnership to all in 2012 rather than extend marriage to same sex couples. It is how the equality issue was addressed in the Netherlands and New Zealand and I agreed with him then.

I would have made civil partnership the mechanism whereby legal rights were granted and left marriage to become an optional extra for people of faith.