In the first of two linked guest posts, Celia Kitzinger explains the problem with the confusing and inconsistent way Court of Protection cases are currently listed, making it more difficult for public observers to attend the hearing.

(This post is reproduced with thanks from the Open Justice Court of Protection Project blog. The second post, written as an appendix, appears here: Why are so many Court of Protection hearings labelled “PRIVATE”?)

This was an exceptionally opportune hearing to observe because (although I must have seen it many times before) I’ve never really paid detailed attention to what happens in court when the judge considers an application from family members to become parties to a case.

I wanted to be clear about the process of judicial deliberation on this issue because “Anna”, the daughter of a protected party in a forthcoming Court of Protection hearing[i], has made an application to become a party. She asked me what it would be like when the judge considered her application in court.

I wracked my brains. I knew I had seen these applications discussed frequently in court, and mostly approved, but I couldn’t remember any of the details. I guess that’s because they simply hadn’t registered with me as ever having been controversial or difficult in any way.

So, I was very happy to discover, after I joined this hearing (COP 1388671T), before District Judge Dewinder Birk in Leicester), that it concerned an application for party status from family members – and as soon as I could, I cleaned up my notes and sent them over to Anna.

I’ll spell out what happened in relation to the family application in this blog, in case it’s of use to other family members who would like to be parties to a case.

But before I do that, I want to say something about why I asked to observe this hearing – and my frustration with the way it was listed, which was, sadly, typical of many listings.

So, Part A of this blog post is about the way this hearing was listed and how it exemplifies the way court lists undermine the judicial commitment to transparency. If you just want to read about the hearing itself, go straight to Part B, “Family applications to be joined as parties”.

Part A. Listing this hearing: Problems for transparency and open justice

It’s extraordinary to me that the Court of Protection – a court with “transparency” as a central philosophical principle – produces court listings entirely unsuited to delivering on its stated objectives.

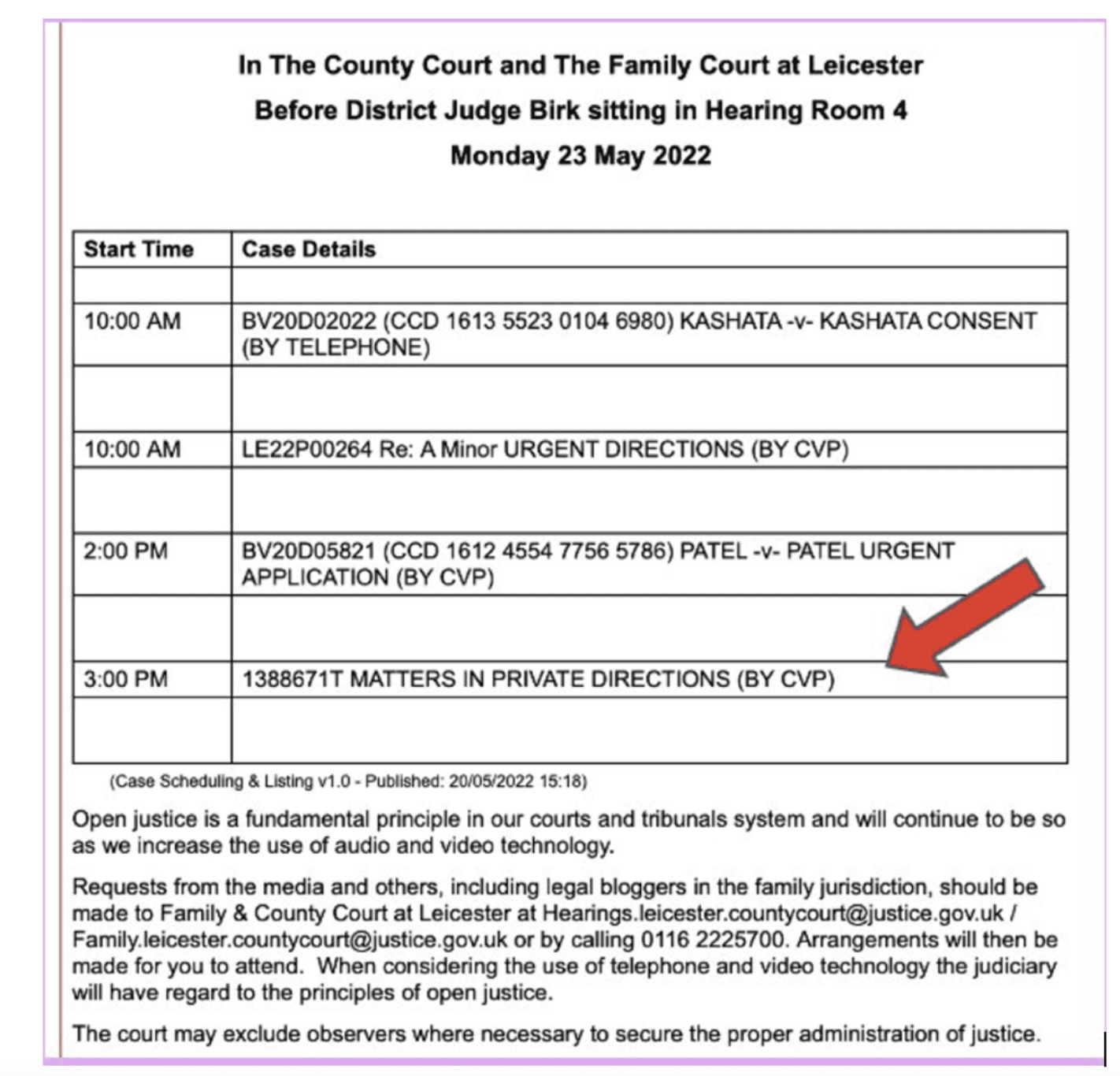

Here’s how this hearing appeared in CourtServe, the live court listings service that members of the public have access to (for free) to check on hearings.

This court hearing did not appear in the Court of Protection lists. Nor is it labelled as a Court of Protection hearing in the county court list in which it did appear (as a ‘hidden’ hearing). That’s not remotely transparent. If it’s not in the Court of Protection list (or at an absolute minimum, labelled as COP in some way) how will most people even know of its existence? It’s also designated “PRIVATE”, and omits any mention of the issues before the court, And (if all that were not deterrent enough) it provides incorrect contact information. (These failings are spelled out in detail below – where I also explain how common it is to find failings like this in the Court of Protection lists.)

If there were, as some commentators have claimed, a conspiracy afoot, from a “secret and sinister” court, to obstruct public attendance at hearings, this is a good candidate exemplar.

I don’t think there is any such conspiracy – and I did get to watch this hearing and am now blogging about it publicly.

I accept that the judiciary is truly committed to transparency. But it’s staggering to find – repeatedly, consistently, on such a wide scale and over the course of nearly two years – such a big gap between the judicial commitment to transparency and actual practice on the ground.

I’ve been writing publicly about problems with the court listings since August 2020 – and tweeting about particular instances, expressing my concern in talks before lawyers and judges, and sending written complaints to relevant persons and organisations. Nothing much has changed.

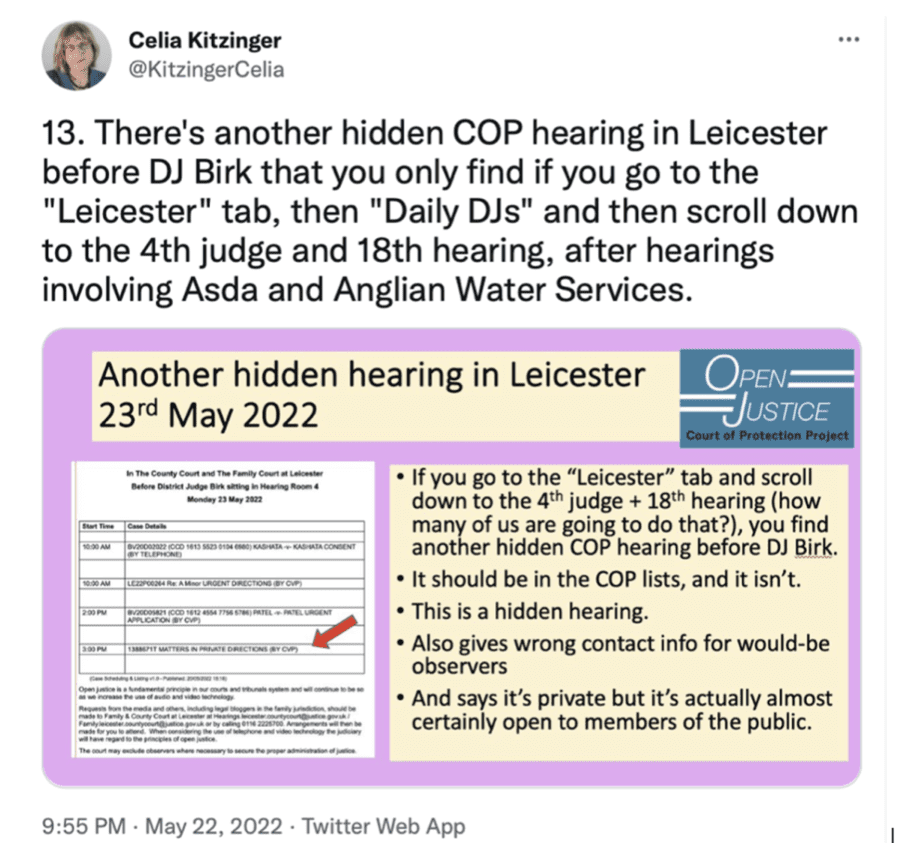

The way this particular hearing was listed exemplifies a lot of the problems, and I tweeted about it the day before, after completing a systematic search of the listings to test and to document my (repeated) claim that there are serious problems for open justice with the way hearings are listed.

Here’s the tweet I posted. (It’s part of a long tweet thread – no. 13 of what turned out to be 22 tweets-with-slides.)

In relation to transparency and open justice, there are four really serious problems with this listing, alluded to on the tweet above, and spelled out below.

1. It’s a hidden hearing

First, and most serious of all, it was not in the Court of Protection list for 23 May 2022.

Members of the public who want to observe a Court of Protection hearing should be able to go to a single site where all the hearings are listed. Then they can look down the list and decide which one they want to observe.

But over the time I’ve been systematically checking the listings, I’ve found that anything from a quarter to a half of the hearings don’t actually appear in the Court of Protection list. Instead, they are scattered throughout CourtServe under the names of towns and cities or judges. It’s extremely time-consuming to find them – there are literally hundreds of hearings! – and most days when I want to observe a Court of Protection hearing I don’t bother. I simply go straight to the Court of Protection list – even though I know full well that only half the hearings may be recorded there.

This particular hearing was listed under a subheading under the top-level heading “Leicester” in the general county court lists. These lists feature hearings very different from Court of Protection cases. Some of those I scrolled through were cases involving children, or divorce. Others were small claims hearings and financial disputes. Asda supermarket was listed as a party in one. Anglian Water Services was a party in another. Clearly, I was well outside Court of Protection territory!

There were 3 subheadings under “Leicester”, one of which was “Daily District Judges” (there was also “Daily Circuit Judges” and I can’t now remember what the third one was). I clicked on all three subheadings in turn and scrolled down through dozens of listed hearings, looking for “Court of Protection” or “COP”.

There was nothing listed as “Court of Protection” or “COP” under any of the three subheadings.

But my eye was caught by this hearing (listed under “Daily District Judges”) because – even though it doesn’t say it’s a Court of Protection hearing – it “looks like” a COP case number.

Not many members of the public know what a Court of Protection case number “looks like” but over the course of the last couple of years I’ve come to recognise the pattern. Most COP case numbers consist of 8 digits – all numeric, none alphabetic (though P’s initials are often appended to the 8-digit number) – and during the time I’ve been watching remote hearings they’ve mostly started with 135, 136, 137 or 138. (The most recently issued cases start with 139, and I expect to see case numbers starting with 140 before the end of the year.)

This one didn’t quite fit the pattern. It’s only 7 digits and there’s a T at the end. But I also know that those numbers ending in T do crop up occasionally – I’d noticed and asked why back in May 2020.

Nobody knew!

As I illustrated in a subsequent tweet, even eggs come with helpful keys to understanding the codes stamped on them. But for Court of Protection hearings, it’s just one of those mysteries.

It was unusual for me to be looking for Court of Protection hearings outside of the COP list – I only do it once a month or so, so as to be able to document the ongoing problems in the (possibly quixotic) hope that this might result in change.

So, because of the way this hearing was listed, I normally wouldn’t have had the opportunity to observe it. I simply wouldn’t have known it was happening. Nor would anyone else, except the people directly involved.

If another member of the public had been looking outside the COP list for a COP hearing (an unlikely scenario), I doubt they’d have recognised it as a COP hearing: my obsessive scouring of listings over the last two years has given me unusual powers!

So, I decided to ask to observe it precisely because it had been so well hidden in the lists – I was determined not to allow listing failures to consign it to obscurity.

Also, by asking to observe it, I’d find out for sure if it was a COP hearing or not

2. It’s a “PRIVATE” hearing

Way back in 2016, shortly after the beginning of the Transparency Pilot Scheme, Mr Justice Mostyn said:

“I want to dispel the idea, which continues to be peddled by certain sections of the press, that the Court of Protection is a secret, sinister court which dispenses justice behind closed doors.”

It beggars belief that a court so determined to counter the impression of secrecy should label so many hearings “PRIVATE” – creating an entirely illusory impression of secrecy where in fact none exists.

Members of the public can be (and in my experience are) admitted to almost all the hearings labelled “PRIVATE”. (See Appendix post: Why are so many Court of Protection hearings labelled ‘PRIVATE’?)

I’ve spent a lot of time explaining to this to would-be observers – to their disbelief and bewilderment. Here’s a tweet from two years ago, again part of a thread about the day’s CourtServe listings.

I think the small print at the bottom (check out the photo of the listing) about “Open justice” is designed to counter the impression created by the words “IN PRIVATE” – but it simply doesn’t work!

Why would anyone be surprised that the word “PRIVATE” has a chilling effect on open justice?

3. There’s no information about the issues before the court

As I said earlier, I didn’t know what this hearing was going to be about when I asked to observe it.

That’s because no information was provided in the list about the issues before the court in this hearing: they are unhelpfully referred to as “MATTERS”.

Anyone who’s been following my Twitter feed – or @OpenJusticeCOP – will already know that the absence of information about what hearings are about is very common in Court of Protection listings – the norm, rather than the exception.

There was a clear official statement, when the Transparency Pilot was launched more than six years ago now (on 29 January 2016) that descriptions of the issues before the court would be made publicly available in listings.

“Policy officials will also work with Her Majesty’s Courts and Tribunals Service to amend the way in which court lists are displayed, so that they provide a short descriptor of what the case is about, allowing the media to make an informed decision on whether to attend the hearing.”

https://www.judiciary.uk/wp-content/uploads/2015/11/cop_transparency_pilot_background_note_19.11.15.pdf

Nearly eighteen months later, this still hadn’t been achieved, and the judiciary seemed unsure about how to go about implementing it. The (then) Vice President of the Court of Protection, Mr Justice Charles, said:

It is recognised that it is important that cases are appropriately described when they are listed to provide information to the public at large of what they are about and when and where they will be heard. Comment on how this should be and is being done is welcomed. As is more general comment on how the public and the media can make themselves aware, or should be made aware, that certain types of case are due to be heard…

https://www.judiciary.uk/publications/the-transparency-pilot-a-note-from-the-vice-president-of-the-court-of-protection/

It’s still the case that many (sometimes most) lists don’t have any indication of what hearings are about. None of those posted on the Royal Courts of Justice website ever does – and it’s proved enormously frustrating for health and social care practitioners, activists and educators who have special interests in observing hearings on particular issues.

For example, court-ordered Caesarean sections (and other court orders related to mode and place of birth) have been of particular concern for some midwifery groups and for the charity BirthRights, dedicated to “protecting human rights in childbirth“. These hearings raise key issues related to autonomy over our bodies and reproductive rights. But without advance information (sometimes sent to journalists but not to us!) about when these hearings are being heard, it’s unlikely that we’ll get to observe them and impossible to plan to do so. That’s a real problem for open justice, and creates exactly the impression the court wants to avoid – of a secret court ordering restraint and surgical interventions on resisting pregnant women. Check out my blog about one such hearing, where I make the point that:

“it’s not sufficient for open justice to have to rely on reports from journalists. Media accounts are necessarily abbreviated versions of complex decision-making processes. Journalists cannot be expected to engage with these issues in the same way as a consultant obstetrician, a specialist perinatal community mental health midwife, a feminist psychologist, or an expert by experience. There are limits to the extent to which a journalist can act as the ‘eyes and ears of the public‘” .

(Agoraphobia, pregnancy and forced hospital admission)

Finally, simply in terms of encouraging the public to support the principle of open justice and perform the civic duty of observing hearings, I have to say that I find it hard to persuade or entice members of the public to give up their time to observe a hearing when I can’t supply them with any information about what they’ll see. It’s like trying to sell theatre tickets without telling us which play is being performed.

4. The contact information is incorrect

Suppose a member of the public actually found this hidden hearing and recognised it as a COP hearing, understood that “PRIVATE” wasn’t intended to deter the public from attending, and was interested despite no information about the “MATTERS” to be addressed in court. Now they would need to send an email asking for the link. The obstacle course continues!

The correct email address from which to request access to Court of Protection hearings is the email address for the Regional Hub with which any given court is associated. The Regional Hubs are listed on a gov.uk webpage (here).

For this court (Leicester), would-be observers should contact the Midlands Regional Hub, which has a Birmingham email address (courtofprotection.birmingham.countycourt@justice.gov.uk).

But the list gives two email addresses in Leicester.

Incorrect contact information is common when Court of Protection hearings haven’t been included in the Court of Protection list.

On this occasion, in a spirit of enquiry, I emailed the two Leicester addresses, just to see what would happen.

Usually, when I’ve (inadvertently) sent emails to the wrong addresses (as given on the listings), the outcome has been no response, or a very delayed response, after my email has been forwarded to the correct address – sufficiently delayed, in fact, that I miss the hearing.

I sent this enquiry to the wrong addresses more than 3 hours before the time the hearing was due to start. I figured if I didn’t hear back (or got an inappropriate response), there was still time to contact the correct address. I was pretty surprised to actually receive the link to observe the hearing a couple of hours later – just before 2pm (which was when I’d planned to resend the email to the correct address). A clerk at Leicester had forwarded my request (marking it “URGENT”) to someone designated as a “CVP Court Clerk” (CVP = Cloud Video Platform) for DJ Birk that day, and that person had sent me the link. (Many thanks for the prompt actions of the people involved.)

These are not the actions of people determined to exclude the public!

When Anna read the draft version of this blog, she commented: “With regards to the wrong email address you noticed , one thing that occurred to me is that you are now well known in legal circles re COP cases ( I could tell this from attending the hearing with you!). Would an ordinary member of the public be given the hearing link so quickly, I wonder.” I share that concern. I think sometimes I get special treatment.

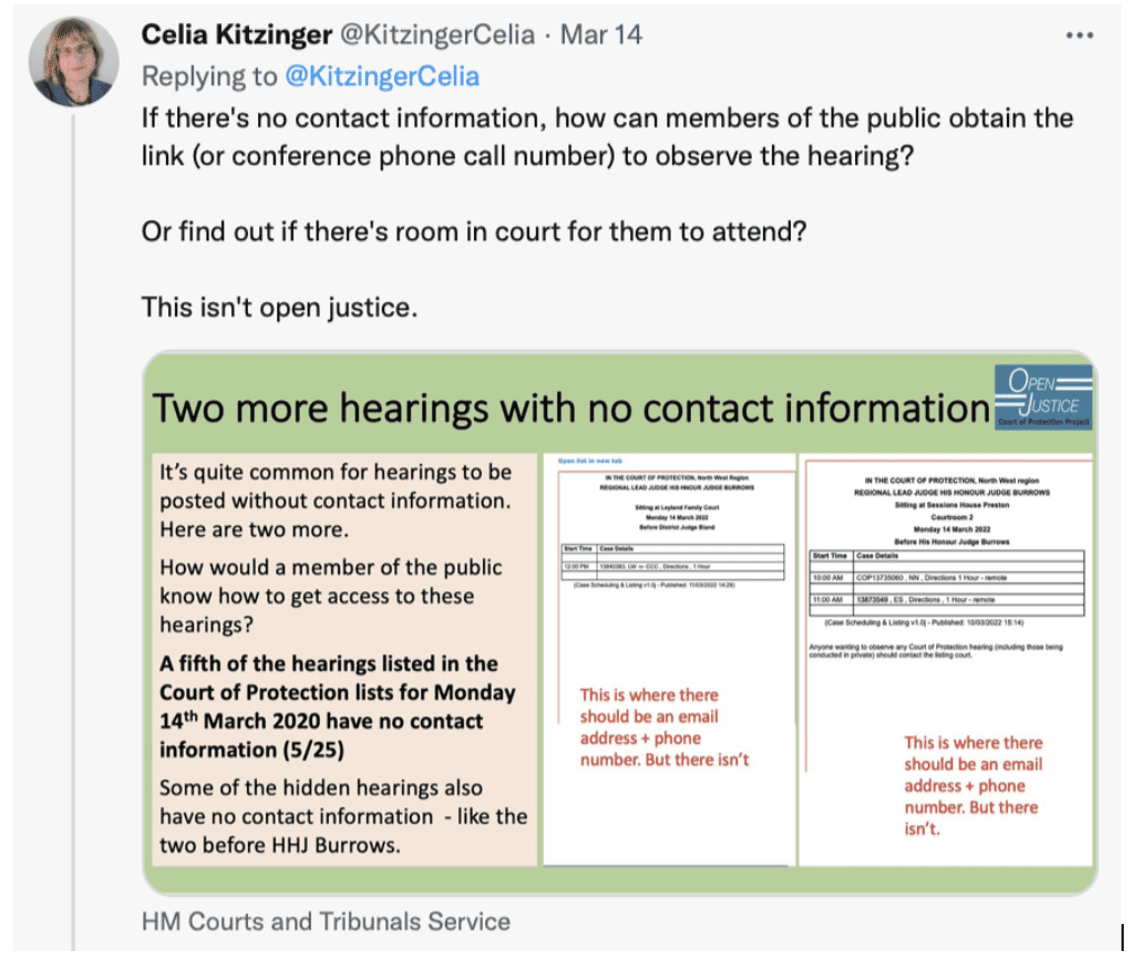

I’m baffled as to why the lists so frequently get the contact information wrong – or omit it altogether.

Let me show you some other examples I’ve tweeted about over the years.

For a while, the court seems to have been using a template requiring people submitting to the listings to complete their own Regional Hub email address. They weren’t doing it – and the email address kept appearing as COPhubemail (which was intended, presumably, to signal “fill in your own COP Hub email address here“)

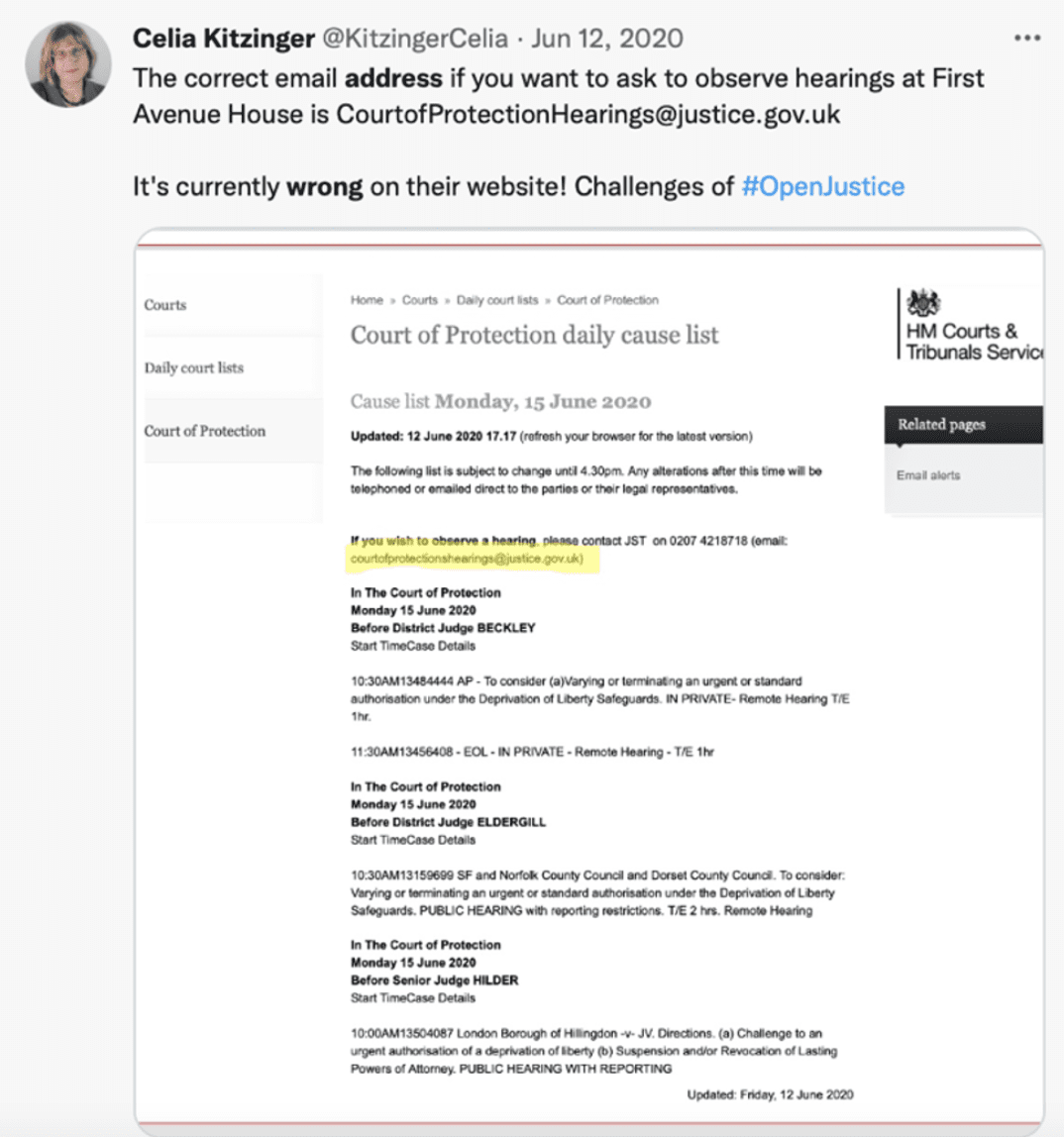

Then there was a week or more when First Avenue House in London was displaying the wrong email address (there’s an errant ‘s’ that’s crept into the middle of it) – so would-be observers kept contacting me to say their emails were bouncing back.

Recently, I discovered from a systematic search that 20% of CourtServe entries omitted contact information altogether (again this tweet is part of a thread which covers listing problems on 14 March 2022).

I’ll return to these listing problems in my “Final Reflections”.

Part B: Family applications to be joined as parties

This was the first attended hearing in the case and the first at which P was represented.

The two existing parties were the applicant local authority (represented by Mark Kamlow) and the protected party (P), represented by Lauren Crow of MJC Law, her Accredited Legal Representative (ALR).

P’s mother and grandparents were there (attending together from a single location) and they all wanted to be joined as parties.

I later learnt from the Position Statement on behalf of P that these family members oppose the local authority’s application for a declaration that it’s in P’s best interests to move from her grandparents’ home to supported living accommodation. P herself also consistently says that she would like to remain living at home with her grandparents. But the local authority is concerned about the quality of the care she receives there.

There were issues to discuss and orders to make in addition to the question of family representation, and these were dealt with first.

The most significant was appointment of an independent consultant psychiatrist to complete a capacity assessment of P (a teenager with spina bifida, hydrocephalus and “learning difficulties”) to see to what extent she is able to make her own decisions. Obviously, the court has no jurisdiction to tell P where she must live unless it’s determined that she lacks capacity to make this decision for herself.

The only existing evidence on capacity is over 18 months old and relates solely to P’s capacity to conduct legal proceedings. There is no evidence of P’s capacity to make decisions about where she lives, the support she receives, who she has contact with – or about her capacity in relation to financial matters and whether (should it become relevant) she can sign her own tenancy agreement.

In addition, there were some third-party disclosure orders and timetabling matters to sort out (and the need, since I was observing the hearing, for a Transparency Order).

The two legal representatives were agreed as to the “general direction of travel” in relation to these substantive issues.

The judge also asked each of the legal representatives for their view on party status for the family members.

For the local authority, Mark Kamlow said:

“We are content for them to have party status. This will enable them to participate as actively as possible and allow them to see the expert reports and comment on them. Hopefully it might assist in terms of seeing solicitors and getting them their own legal representation.”

For P, Lauren Crow said:

“We have no objection to them being joined as parties, but there will need to be some slight redrafting of the expert instruction to ensure they are not responsible for the cost of that.”

(Expert instruction is usually shared equally between parties but it’s common for family members who are parties NOT to have to pay their ‘share’ of this.)

Having established all this, the judge turned to the three family members. She had previously greeted them at the beginning of the hearing, checked they could hear everything, and said that she knew they had applied to be joined as parties and she would deal with that shortly.

Now she checked that they understood what was involved. “If you were parties, you’d need to attend all future hearings, and will get the papers. Is that what you would want?”. All three said yes.

The judge then said, “Well, I have no objection, because you are obviously very much a part of P’s life and need to know what’s happening. So, what the court will do today is make you parties, alright?“. They all said “yes“.

Then she checked their position on the other declarations and orders the court was going to make today.

Judge: We are going to gather some information. One piece of information is the expert report. Have you got anything to say about that?

Family: No.

Judge: We are also going to get further information about P from her medical records – anything you want to say about that?

Family: No.

Judge: Then we’ll come back after all that information’s been gathered, and you’ll be able to read all the information that’s been gathered, and the court will hear from you about what you think of it. Are you happy with that?

Family: Yes.

There was then some discussion about the time and date of the next hearing, and whether it should be remote or in person. The family had requested an in-person hearing and this was agreed. The next hearing (a ‘case management hearing’) is planned for 19 October 2022 at 2.00pm before DJ Mason in person in Leicester County Court.

Lauren Crow said she would “explore with P as well whether she would like to attend” (she wasn’t at this hearing).

Finally, the judge addressed the family, asking “Anything further? Is there anything you’d like me to explain about the orders I’ve made today, or anything else you want to raise?“. They said no, and the judge ended by saying that the local authority legal representative would be in touch with them to provide them with the documents for the upcoming hearing, and would also try to help them to find legal representation.

So that was straightforward! And typical of the sort of thing I now realise I’ve seen many times before.

Often, family members are named as respondents from the outset of a case (and confirm a wish to be formally involved), so there is no judicial determination as such. When they are not so named, but wish to be joined as parties, there are some “rules” and case law to assist the judge’s decision[ii].

Rule 9.13(2) Court of Protection Rules 2017 is the test for joinder of any party. It says simply: “The court may order a person to be joined as a party if it considers that it is desirable to do so for the purpose of dealing with the application.”

Case law helps with understanding what might count as evidence that joining a party would be “desirable”. Simply being a family member doesn’t give rise to an “entitlement” or “right” to be joined as party but if joining that person would to help to ensure that P’s interests and position are properly considered, then it would be “desirable” to join them (Re KK [2020] EWCOP 64).

A judge making a decision about joining someone as a party is supposed to balance the pros and cons in the particular circumstances of any given case – and joining a family member who knew P well before P lost capacity could be beneficial in enabling the judge to better take into account the protected party’s wishes, feelings and preferences.

42. By R.73, the court may join a new party if it considers that it is “…desirable to do so for the purpose of dealing with the application.” The clear import of that wording is that the joinder of such an applicant would be to enable the court better to deal with the substantive application (for example, by its being able to take into account and test the views of a close relative who knew the incapacitated person and was familiar with his wishes, feelings and preferences before he became incapacitated).

43. The word “desirable” necessarily imports a judicial discretion as regards balancing the pros and cons of the particular joinder sought in the particular circumstances of the case.

Re SK [2012] EWHC 1990 (COP)

I shared all of this information, along with my notes from the hearing itself, with “Anna”, the daughter of a protected party in another case, so that she would understand the basis on which a decision would be made about joining her as a party in her mother’s s.21 case. Anna’s response was heartfelt:

“Gosh, thank you so much for this information. I feel quite daunted by this process of joining as a party, on top of everything else to do with the case, and knowing more about it is really useful and reassuring for me.” (Anna)

For Anna, the situation is a little more complicated because (as she said in her original blog post), her sister holds lasting power of attorney for their mother (both for Health and Welfare and for Property and Finance). Anna tells me the local authority’s solicitor has put pressure on her sister (however unintentionally) to become a party – instead of (or as well as) Anna – and her sister is now worried that the judge will insist on this, despite the fact that all four of P’s adult children, including P’s LPA, believe that Anna is the right person to be a party in the case and is best able to represent the views of the family. The issue of the relationship of LPAs and party status in hearings is (as Anna says) something solicitors (and health and social care professionals) need to be sensitive to in dealing with families. She asked me to feed this back through my blog.

All in all, this was a really valuable hearing for me to observe – both for my own legal education, and (indirectly, through me) for Anna as a court-user for whom this information is of immediate practical relevance. I just wish I had known what the hearing was about in advance, and I could have invited Anna to join me and witness it at first hand.

Final Reflections

Many people who contact the Open Justice Court of Protection Project believe that the court is deliberately obstructive of open justice. I understand why it can feel like that.

It takes an effort of imagination to realise that problems of transparency are caused not by deliberate intent, but because of systemic failings in the necessary infrastructure needed to support open justice. Open justice fails despite the judicial commitment to it.

It really isn’t the case that the lists are deliberately designed to discourage us from observing hearings. It’s just that – very often – they have that effect.

Having attended this hidden and “private” hearing, I can’t detect any reason why anyone would have sought to exclude me: there was nothing ‘secret’ or ‘sinister’ about it at all.

There’s a maxim called Hanlon’s Razor[iii] which appears in different versions, including: “Never ascribe to malice what can adequately be explained by incompetence”. Without wishing to be heard as accusing the Court of Protection of incompetence, I have found this a useful maxim to bear in mind in my dealings with the court. The most likely (parsimonious) explanation for failings in open justice is because – in large part due to chronic under-resourcing of the court service – the daily court listing service hasn’t been updated, as had been proposed, with the advent of the Transparency Pilot. And staff haven’t been trained in what’s needed, are overwhelmed by their workload and don’t get to read emails in time. It’s perhaps surprising – and testimony to the good intentions of court staff, lawyers and the judiciary – that we get to observe as many hearings as we do!

But good intentions are not enough.

The inadvertent exclusion of the public is as damaging for open justice as if it were done deliberately.

The reality is that sincerely-held and lofty ideals of open justice depend upon mundane and tedious everyday details like adequate listings and responding to emails in a timely fashion.

It’s glaringly apparent that the listing system wasn’t set up in an outward-facing user-friendly way for members of the public. It needs a thorough overhaul.

What if there were an official public-facing Court of Protection page on a gov.uk website explicitly welcoming observers to attend hearings and explaining how to understand the lists and what to do to get to court?

What if the lists included information about what hearings were about – including user-friendly descriptors like “Family application to become parties” or “Caesarean-section” – to attract court-users with particular (personal or professional) concerns?

What if there were an official gov.uk page for the Court of Protection with some Q&As answering questions like Anna’s “How will the judge decide whether or not someone can be a party to a case”? (This is especially important of course given the large number of litigants in person.)

Then we might have a truly transparent Court of Protection – both improving access and knowledge of the way the court works for members of the public in general, and more particularly for those involved in Court of Protection proceedings.

What we need to figure out is how we can all work together to get there from here!

Celia Kitzinger is co-director (with Gill Loomes-Quinn) of the Open Justice Court of Protection Project. She has been observing Court of Protection hearings since 2010 – initially dozens of in-person serious medical treatment cases, and then since May 2020, a wide range of remote hearings (more than 300) in courts across England and Wales. You can follow her on Twitter @KitzingerCelia

Footnotes

[i] You can learn more about Anna (not her real name) and her mother’s case in the blog she and I co-authored after watching a s.21A hearing together. Check out “A section 21A hearing: Impressions from a veteran observer and the daughter of (a different) P in a s.21A case”. One of the points I make in that blog is that it’s fairly easy to find a s.21A hearing for members of the public who wish to observe them, because (a) they are common cases; and (b) they are often heard at First Avenue House London, which operates the only court listing service which routinely and systematically lays out the issues before the court (see “Court of Protection Daily Hearing List”). Bear in mind, however, that, despite its name, this list covers a small percent of the total number of Court of Protection hearings across England and Wales. For a comprehensive listing, you must use CourtServe. And that many members of the public do not know what on earth a “s.21A” hearing would be about – my first response to contact from Anna was to ask whether (based on her description of the case) she had heard the words “section 21A” and then to describe to her what that means!

[ii] Many thanks to the lawyers who responded to my tweet asking “Court of Protection lawyers – are there rules about when/whether family members of P can formally become ‘parties’ to a case? Or case law? Is it a judicial decision? What needs to be considered + why might it be opposed? Relevant links welcome! Thank you.” Many thanks to lawyers Emma Sutton and Ben McCormack, from whom I received helpful and informative answers within the hour citing Rule 9(13)(2) and the case law, respectively. Thank you also to Eleanor Bulmer, who subsequently drew my attention to Practice Direction 9B, Rhi Jones (who drew attention to the matter of costs) and Molly Fensome-Lush who contributed her experience: “The only case I’ve had where a family member wanted to be joined and wasn’t was where P herself vehemently opposed it and spoke to the judge directly to ask him to refuse the application”. Legal Twitter at its best!

[iii] The maxim is attributed to many different people (including David Hume, Ayn Rand, Napoleon Bonaparte and Goethe). The Wikipedia entry says that Hanlon’s razor became widely known as such in 1990 after its use in the Jargon File, a glossary of computer programmer slang, though the phrase itself had been in general usage years before. Its name is inspired by “Occam’s razor” and (probably) by the computer programmer Robert J Hanlon, who publicised the principle. Both Occam’s razor and Hanlon’s razor refer to heuristics designed to prune sets of hypotheses by favouring parsimony.

Featured image: Private / Public via Shutterstock.