This post originally appeared on Medium and is republished with thanks. It’s an explanation of, and commentary about, the recent family court judgment from the former President, Sir James Munby, in FS v RS and JS [2020].

In 1984, the now-defunct Trustee Savings Bank adopted the memorable advertising slogan “The Bank That Likes To Say Yes”. The customers they were saying “yes” to then were paying interest of 12.5% [1] on mortgage borrowing, at a time when average earnings for men and women were about £5,000 per year [2], and average property prices in the UK about £26,500 [3].

By 2012, nearly thirty years later, the phrase “the Bank of Mum and Dad” had entered the dictionary [4], perhaps originally coined as a joke, but now widely and seriously used to describe the phenomenon of “baby boomers” born between 1946 and 1964 providing financial assistance to their “millennial” children born between 1981 and 1996. By January 2019 researchers at LSE [5] found that the Bank of Mum and Dad was among the top ten lenders in the country, and that, although the expression usually refers to assistance to purchase otherwise unaffordable houses or flats, the average price of which is about 10 times what it was in 1984, in fact this only accounts for a fraction of financial support from parents of this generation to their adult children.

FS v RS and JS, a case which made headlines when the judgment was published on 30 September 2020, is a case where the Bank of Mum and Dad said “No” to an adult son who they had been maintaining for decades. FS then asked the High Court to order his parents to maintain him. The judge [6] also said “No”. He described it as “unprecedented” and “a most unusual case”, on a point which many people would be surprised could even be argued, but which had never been decided before in English law. By coincidence, a similar case in Italy [7] reached its Supreme Court at about the same time and came to the same conclusion: adult children — known colloquially as “bamboccioni” (big babies) — without physical or mental impairment and still living with their parents, do not have a legal right to further parental maintenance, but “must strive to make themselves economically independent and adjust their aspirations to the realities of the labour market.”

The decision in FS’s case

The anonymous FS is aged 41, and so was born a few years before 1984 and is not quite a millennial. He has several educational and professional qualifications, including being a qualified solicitor, and is currently studying for further academic and professional qualifications, but has been unemployed since 2011. He has “various difficulties and mental health disabilities … their true extent is not clear”. His parents, who are married and live together in Dubai, and said to be very wealthy, have financially supported him for years, and continue to do so to some extent. He lives in a flat in central London which is formally in their ownership and for which they paid the outgoings until recently. At the time of the hearing in his case, he intended to bring a separate claim asserting that he has an interest in the flat [8]. Both this and FS’s primary claim, which was issued in July 2020 and proceeded with remarkable speed to a hearing on 12 August and judgment on 30 September, appear to have been prompted by a deterioration in relations between FS and his parents, particularly his father, and a significant reduction in the financial support they are prepared to offer him.

The judgment which has been published is a decision only on the legal question of whether or not an adult like FS is entitled to claim the financial maintenance that he seeks. It does not examine any facts in depth, but accepts for the purpose of deciding the legal question that FS is “vulnerable”, a word which has a specific meaning in this area of the law. To the extent that it involves a degree of mental impairment, it is impairment which falls short of positively lacking mental capacity to make personal decisions.

FS’s first argument was that there was a statutory obligation for his parents to maintain him. There are two statutes which contain provisions about parents’ obligations to maintain their children: the Matrimonial Causes Act 1973, which deals with divorce, and the Children Act 1989. Unsurprisingly, the obligations of maintenance largely come to an end when a child reaches 18, at the latest, with some limited exception where the child is in formal education or vocational training or there are “special circumstances”, disability being the most obvious. FS was not eligible to claim maintenance from his parents under either of these statutes. Applications under the Matrimonial Causes Act can only be made by a child of the marriage who is over 18 if there is already an order for periodical payments made on the application of one of the parents. FS’s parents had never been divorced, so neither had ever applied for such an order. Orders under the Children Act cannot be made when the child’s parents are living with each other in the same household, as FS’s parents were. As the judge said, the statutory language is clear, and means what it says, and an excursion into legal history revealed the clarity of the underlying principle that

“children are entitled to provision during their dependency and for their education, but they are not entitled to a settlement beyond that, unless there are exceptional circumstances, such as a disability, however rich their parents are” [9]

FS then argued that each of these statutes should be interpreted, or so far as possible, read and given effect to in a way which is compatible with Convention [the European Convention on Human Rights] rights, as required by s3 of the Human Rights Act 1998. The Convention rights asserted in this case were the right to life (Article 2), the right to a fair trial (Article 6) and the right to respect for private and family life (Article 8). FS himself asked the judge to consider the right to property (Protocol 1, Article 1) as well. The judge said that it would be fundamentally wrong to indulge in this interpretation, because such a reading would conflict with the essential principles of the English legislation, nor could it be argued that any of the English legislation was incompatible with any of the Convention rights invoked on behalf of FS.

The final aspect of the claim, arguing for a positive obligation of maintenance arising out of the High Court’s inherent jurisdiction in relation to vulnerable adults was particularly adventurous, in metaphorical terms following in the footsteps of adventurer Percy Fawcett, far away from the coastline and deep into the rain forest of uncharted legal territory. As the judge explained, the inherent jurisdiction of the High Court is a kind of “safety net” which fills gaps left by statute law. In the years since the Mental Capacity Act 2005 came into force, the court has established that the inherent jurisdiction still exists in relation to “vulnerable” adults who do not lack mental capacity, essentially to protect them sufficiently to be able to exercise that capacity fully [10]. But it does not go so far, nor was the judge prepared to extend it so far as to use it to create a power to compel someone to pay maintenance for a vulnerable adult.

The judge concluded that FS “has no case” and that his claim should be “summarily dismissed.” He refused FS permission to appeal, and ordered him to pay just under £57,500 of his parents’ legal costs.

FS and his parents are anonymous in the judgment, although unfortunately not sufficiently anonymised to be unidentifiable to every reader of it. And even though anonymous, something of FS’s personality as an intelligent but obsessive litigant appears to emerge from the narrative, with extensive attempts to introduce new arguments and persuade the judge to change his mind after he had circulated his draft judgment for typographical corrections, and emails raising new points sent on his behalf as late as the middle of the evening before the judgment was due to be published. The judge, even with long and extensive experience of litigants in the family courts and the Court of Protection to draw on, described FS as “unusually difficult, demanding and pertinacious (very tenacious)”. Coupled with his description of the entire litigation as “unedifying and really rather sad”, it underscores the extent to which the claim exposed FS’s misdirected intellectual effort and misplaced expectations from it, and, in a way, his vulnerability.

“Millennials” v “Boomers”

It is easy to read the decision as a conflict, as in the Italian case, between the economic status and expectations of two generations: “Millennials” and “Boomers”, with the result being, as someone tweeted “a blow for millennials across the nation”. But there may be a sense of entitlement on the adult child’s part inherent in such a conflict, arising from a long-standing dependency created or acquiesced in by the parents themselves. The QC who acted for FS in the claim described his parents (although they did not agree with this description) as “having in fact, whether wittingly or unwittingly, nurtured [FS’s] dependency on them for the last 20 years or so, with the consequence that he is, so it is said, now completely dependent on them”. In one unsuccessful claim for maintenance against the estate of a parent who had died [11], the judge noted the middle-aged daughter’s “strong sense of entitlement” and expectation of inheritance from her aristocratic father, despite a long estrangement from him.

The LSE 2019 report on the Bank of Mum and Dad explored the attitudes of both parents and children, their concepts of fairness and need, and an asymmetry of attitudes between the two –

“Some potential beneficiaries had a (perhaps unspoken) expectation of receiving help, while the respective donors, once they realised the reality of what they had promised or the expectations of all their children, might wonder how and indeed whether they could provide the help they expected”

The judgment in FS makes it clear that even where an adult child’s sense of entitlement or dependency has been encouraged by his or her parents, as FS asserted it had been in his case, it gives rise to no rights simply through the parent-child relationship whilst the parents are alive. It would be different if there was a binding contract or a non-contractual promise which has been relied on to the child’s detriment, which the law may recognise as to some extent enforceable. This is a relatively recent development. In January 1977, a couple of years before FS was born, Lucy Gonin, a woman then in her sixties, brought a claim to the High Court based on an agreement she had made with her parents during the Second World War. Her fiancé had died on active service and she had given up her wartime job to go home and live with her parents and look after them for the rest of their lives, in return for no more than pocket money and a promise that she could have their house and its contents after they died. Her father died in 1957 and her mother in 1968. Her claim to enforce the agreement with her parents failed, and no promise-based claim was pursued, for reasons I have written about at greater length here.

Nor does the law compel a parent to make up to an adult child for failure to act as a parent, or to provide maintenance during their childhood. In 2012 [12], an adult woman known only as D asked the Court of Protection to include her as a beneficiary of a will which it authorised to be made for her wealthy father, known only as JC, who no longer had capacity to make a will for himself. D’s and her mother’s story is an exceptionally sad one. Her mother had divorced JC because of his consistent ill-treatment of her and her young son from a previous marriage, and in 1957 was living alone and in poverty with the two little girls she had with JC. D’s birth was the consequence of a post-marital rape by JC, and her mother gave D up for adoption when she was only a few days old, believing that she would have a much better chance in life if she was adopted. As an adult, D made contact with her birth family, but never met JC. She did not pursue contact with him, and he did not wish to have contact with her, even questioning whether she was his daughter. The Court of Protection refused to include her as a beneficiary of the statutory will, given her father’s probable wishes and her own decision not to pursue contact with him. In 1993 [13], David Harlow, a fifty year old successful businessman with a comfortable standard of living, asked the Family Division of the High Court to order reasonable financial provision for him from the estate of his father, Derrick Jennings, who had died in 1990 leaving his estate to charity. David Harlow’s parents had divorced when he was only four years old, and his mother had remarried. David had had no contact with his father, and his father had provided nothing for his maintenance in childhood. The judge awarded David £40,000, which was about 12% of his father’s estate, because he had not been maintained as a child by his father. The Court of Appeal reversed this decision, making it clear that the reasons which might justify ordering financial provision out of a parent’s estate for an adult child could not include failure by the dead parent to carry out obligations and responsibilities during the son’s childhood which had had no lasting effect on him.

The obligations of the living and the obligations of the dead

Although David Harlow’s case was ultimately unsuccessful, the law under which he brought it did at that date and still does give adult children the right to ask the court to make an order for reasonable provision for their maintenance from the estate of a parent who has died legally domiciled in England and Wales. This law is the Inheritance (Provision for Family and Dependants) Act 1975. Under the original legislation, the Inheritance (Family Provision) Act 1938, the only adult children eligible to claim against their parents were unmarried daughters and sons and daughters incapable of maintaining themselves because of some physical or mental disability. Under the 1975 Act, all adult children are eligible to claim, and whether or not their claim will succeed and to what extent, depends entirely on the court’s value judgment of all of the factors relevant to every 1975 Act claim. It does not simply follow from the fact that an adult child asserts a need for maintenance and an estate is sufficiently large to provide it. A very recent case [14], dismissed as being “absolutely hopeless” in view of the size of the estate and the compelling competing needs of the adult daughter’s stepmother, has sparked debate about other adult children’s claims being pursued without any reasonable prospect of success, and settled at too generous a level through mediation because of the costs risks of even a successful defence at trial.

In the spring of 2017 [15], the claim of Heather Ilott, a woman in her 50s who had been largely estranged from her mother since she had left home as a teenager, against the charities to whom her mother had left her estate, reached the UK Supreme Court after years of litigation, and restored the relatively modest order originally made in her favour. As Lady Hale said

“This case raises some profound questions about the nature of family obligations, the relationship between family obligations and the state, and the relationship between the freedom of property owners to dispose of their property as they see fit and their duty to fulfil their family obligations. All are raised by the facts of this case but none is answered by the legislation which we have to apply”

and she used her speech to explain how unsatisfactory the law was. In doing so, she observed that

“The law has not, or not yet, recognised a public interest in expecting or obliging parents to support their adult children so as to save the public money.”

This proposition was tested in FS’s case. His QC characterised FS’s parents’ stance towards his claim as seeking to shift any responsibility for his maintenance in from themselves to the state, arguing that the court should reject that, as a matter of public policy. FS’s parents did not accept that characterisation of their position, and it received no endorsement from the court.

The failure of FS’s case not only has some echoes of some of the adult children’s claims for provision on the death of a parent, but also marks a clear dividing line between the absence of any legal responsibility for a living parent to maintain an adult child, and the continuing presence of a potential responsibility for the estate of a dead parent to do so.

Footnotes

[1] Rate advised by the Council of the Building Societies Association in July 1984

[2] Based on a 35 hour week of average earnings of £3 per hour taken from the ONS New Earnings Survey of 1984

[4] It was added to the Open Dictionary, a crowdsourced element of the Macmillan Dictionary in 2012, as discussed here

[5] The Bank of Mum and Dad: how it really works — LSE January 2019

[6] Sir James Munby, who was President of the Family Division of the High Court and of the Court of Protection until his retirement as a full-time judge in 2018, and therefore a judge of outstanding experience and knowledge of family law

[7] Ordinanza no 17183 of 14 August 2020, summary of ruling made on 16 July published on website of Corte Suprema di Cassazione with link to PDF of judgment (in Italian) and reported in English here

[8] The order made by the judge on 30 September 2020 imposes deadlines on FS for notifying the court and his parents’ solicitors whether he intends to pursue this claim, and for issuing it if he does decide to pursue it.

[9] Hale J in J v C (Child: Financial Provision) 1999 1 FLR 152, 155

[10] For example, by injunctions preventing an adult son from threatening or coercing his elderly parents in relation to decisions about their property and personal welfare, in DL v. A Local Authority [2012] EWCA 253

[11] Wellesley v Earl Cowley [2019] EWHC 11

[12] Re JC, D v JC [2012] MHLO 35

[13] Re Jennings [1994] Ch 286

[14] Shapton v Seviour 6 April 2020

[15] Ilott v. Blue Cross [2017] UKSC 17

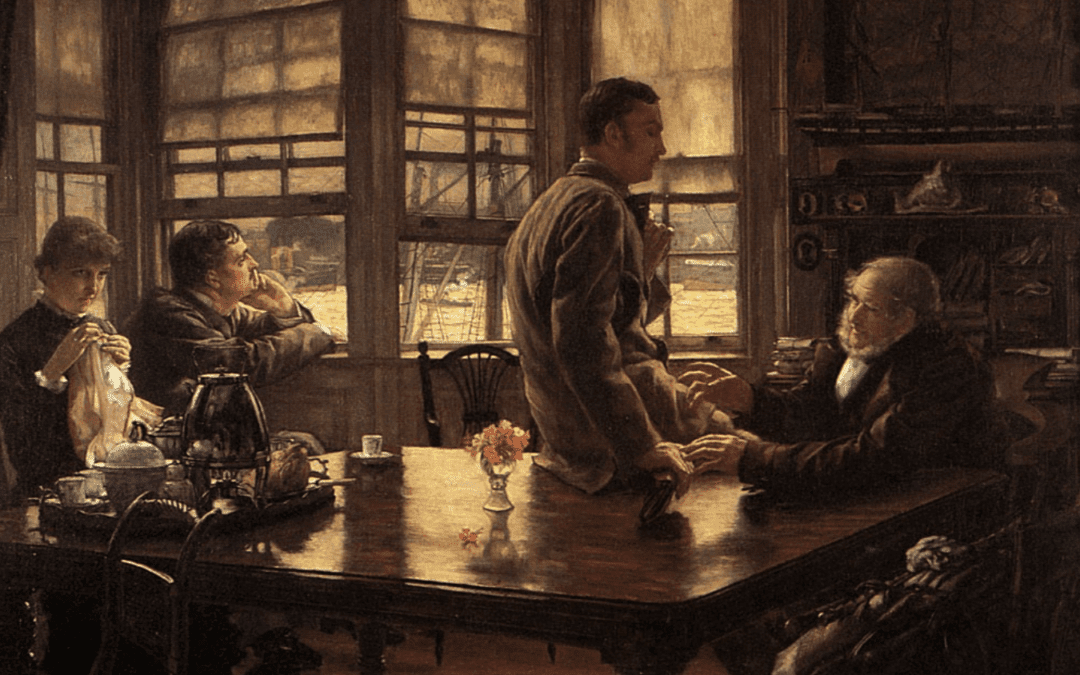

Image – The Prodigal Son in Modern Life – James Jacques Joseph Tissot (1836–1902) — Musée des Beaux-Arts de Nantes -In this interesting blog, art historian Allyson Healey discusses Tissot’s series of paintings and the parable on which they are based, both in their period, and in the context of contemporary intergenerational misunderstandings between “millennials” and “boomers”