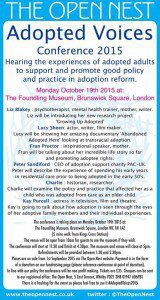

The Open Nest held an intriguing conference on Monday as National Adoption Week began:

It gave a platform to the voices of some adults who were adopted as children; just at the moment that adoption agencies across England and Wales are filling media channels with a narrow, punchy message that children need more adopters to come forward quickly (particularly those over 4 years old for whom it is harder to find families).

First briefly on the theme of National Adoption Week: ‘Too old at 4?’

There is of course nothing wrong (and everything right) with a recruitment drive for adoptive parents for older children if this is what is needed. There’s also nothing wrong with making that message simple, emotive and direct for maximum impact.

But see Sally Donovan in Community Care yesterday The Great Adoption Mismatch for why the answer to secure permanence for those children who are ‘waiting’ in the system may not be just recruiting more adopters after all. And see ‘everywhere’ this week for adverts for adopters, for the most part not even mentioning the extra resilience, capacity and support likely to be required to meet the needs of most of these children.

See also When it comes to Adoption Reform are good intentions enough? in Community Care on the wider question of why so much priority and so much of the adoption reform fund are going to adopter recruitment by contrast to hard adoption support on the ground for children and families.

And anyway why isn’t it transparently called ‘National Adoption Recruitment Week’?

And so onto the Adopted Voices Conference itself

One of the things the Conference tried to do was look at barriers that might be preventing the voices of a wide range of adults, adopted as children, informing adoption research and policy.

Compared with other adults involved in the adoption system – adopters, prospective adopters and professionals, adult adoptees say their voices are almost absent.

“There is no independent adult adoptee on any of the expert boards driving the changes” says Amanda Boorman, Director of the Open Nest, writing in Community Care, When it comes to adoption reform are good intentions enough?

Just how child-centred can an adoption reform programme (or its under-pinning research) be, without taking account of the voices of adults adopted as children, the Conference asked? That does seem a reasonable question.

By contrast, the Conference allowed the lived experience of adult adoptees to be heard, as part of a wider aim of promoting good practice and policy in adoption reform.

The experiences were compelling, powerful and deeply personal. They simply could not have been told without significant courage as well as generosity on the part of those who shared them.

To give a tiny snap-shot of the range and relevance for adoption policy, we heard about:

- How ‘multiple bereavement and overpowering grief’ (upon removal for adoption from a loving foster family as an older child, rather than harm by birth parents or experience ‘in the care system’) became the defining event of a child’s life;

- Of collateral damage done, by severance of multiple relationships (‘no contact’); and the vital importance of maintaining positive relationships wherever possible;

- About what it felt like to ‘wait’ in care for an adoptive family;

- And to wonder whether it could have been different if someone had just done the right piece of skilled work with a birth parent at the right moment;

- Of struggles for adoption support through childhood and into adulthood, including so as to break away from abusive birth families where necessary and to manage the impact of past experiences (‘trauma’)

- About the complexity of finding a secure, meaningful identity as an adopted child (and feelings about names);

- And about the particular complexity of trans-racial adoption in that process.

The central importance of child-centred decision making and listening to children (or not), was apparent in each profoundly different experience.

The Conference also launched research to gather the experiences of a much larger group of adopted adults, including on identity. The research is called ‘Growing Up Adopted’ and more information is available to all adopted adults at: growingupadopted@gmail.com

The Q&A also revealed some interesting views of adoption social workers on difficulties they are regularly experiencing on the ground for children – including problems with adoption agencies routinely letting letterbox contact lapse; and the challenges of current law and practice on imposing requirements on adopters about contact, let alone enforcing them.

The Conference seemed to me to stand in solidarity with some whose lived experience jars uncomfortably at times with government adoption rhetoric, as played out through state funded adoption agencies – at a time when that may feel particularly acute: ‘National Adoption Week’. And I was happy to be part of that.

Thanks Alice, that was very interesting. I wish I had been there. Glad to see more voices added to the conversation and challenging the very simplistic rhetoric we have been hearing much of late.

I’d echo everything you say, particularly around grief, loss, complexity, waiting and the rejection that brings with it. Skilled work with parents is challenging in current timescales, it is there but not enough. We need more courts like the FDAC but focussed on other issues such as LD, DV, oh we love our initials in SW! Or for the FDAC template to be applied so that those courts can deal with other matters in the same way. I would like to hear more from adoptees, some work is done around this, at Coram for example. I would particularly like to hear from those who have been adopted in the past 10 or 20 years when we can, when the landscape of adoption has changed significantly, and we are almost solely removing children from risk.

Julie Selwyn’s book Beyond the Adoption Order shows how difficult it is to find/talk to young adopted people. The parents in her studies had adopted 10 years ago. That doesn’t seem long ago to me and I was taken aback by their experiences of the process (as you might be if you are old enough to have been involved in adoption then). On your main point though, Helen, most of these children had been traumatised, and in some cases this had been glossed over, with adopters uninformed. These were studies about disruption, hasten to add, they don’t represent all placements.

I don’t always check back in the right place for comments but do know Julia’s work. I am surprised by the low rate of breakdowns, I don’t think it can be accurate in so far as it probably doesn’t reflect those families who have the tenacity to continue in order that children don’t re-enter the care system, but perhaps who vote with their feet as teenagers. I wouldn’t dream of challenging info being glossed over, but it wasn’t until I worked with adopters that I understood the trauma of their journey and that their emotional landscape prevented them from hearing.

That isn’t a criticism or even a judgement, 95% of adopters are heterosexual couples who have pursued other methods of having their own children before considering adoption. We are often in effect placing children who have experienced grief, loss and separation (by default because they have been separated from their family of birth) with adults who have experienced a resonant trauma. We have learnt so much in a short space of time particularly about the neurobiology & genetics that we have almost reached a point where we know how much we don’t know. I think we should consider most of our children in care as experiencing PTSD, alongside anything else, and whilst you hope that any issues will be ameliorated by nurturing loving care we can’t predict future outcomes. Being bullied at school can be a trigger etc. Anyway not to waffle on but this is an uncertainty we present to people who have spent a lot of time wanting their own children.