UPDATED 23 AUGUST 2017 to add developments since date of first posting under the sub-heading “The story becomes the story”

Over the weekend of 22 and 23 July I wrote a post about the legal dispute between Great Ormond Street Hospital and the parents of 11 month old Charlie Gard, which was published on 23 July as Kindertotenlieder and the limits of transparency. I felt some trepidation in even beginning to write about a case which had a private family tragedy at its heart, and which had already been so extensively commented on by so many people, but I thought the issues of privacy, public interest and transparency were important, and had at that date not been much discussed. There was an increasing focus and discussion of them during the following week, in which a final hearing of the application to consider new evidence about possible treatment for Charlie had been listed for 24-5 July. This was an eventful week both in and outside the courtroom, starting with the disclosure of Charlie’s parents’ decision to agree that their son’s life-support should be withdrawn as there was no prospect of any further treatment for him, and culminating in the announcement of Charlie’s death in a children’s hospice on 28 July 2017. A timeline of events, with links to primary sources, is in our post of 1 August 2017.

This post is an update on the issues considered in the 23 July post. Court hearings in public continued on Monday, Tuesday and Wednesday of the week of 24 July, with the court sitting in private only for a short time at the end of the last hearing, when Charlie’s mother requested this. The final court order made on 26 July reflects this element of privacy, as it contains some reporting restrictions on the arrangements for Charlie’s end of life, and a confidential annex relating to the detail of those arrangements, which has not been made public.

Continuing media and social media discussion

Both before and since the court proceedings ended on 26 July, extensive media and social media coverage and discussion of the case and its underlying story has continued. It has included publication in the Guardian of an anonymous account from a member of the intensive care staff at GOSH who cared for Charlie, who wrote of the “agonising job” of Charlie’s care team:

Over the last few weeks, parts of the media and some members of the public turned a poorly baby’s life into a soap opera, into a hot legal issue being discussed around the world . . . . this went too far.

It has also included a story in the Daily Mail headed: “Our last hours with our son: Charlie Gard’s parents emotionally reveal how they finally brought their baby home after he died in a hospice and spent several days saying their last goodbye”. Several readers’ comments suggesting that these details should have been kept private received thousands of positive votes, reflecting some public distaste for the decision to share the last moments and posthumous hours of a dying child with the public in this way.

The story becomes the story

Public interest in the way in which the story itself was promoted and reached such a large worldwide audience has also continued. Private Eye drew attention to the fact that the family’s spokesperson and media agent, Alison Smith-Squire, had also written stories published in the Daily Mail under her byline, but without the Mail having mentioned her dual role to its readers. The paper did acknowledge this in its 28 July article on “the colourful cast behind the drama” saying of her

[She] has faced criticism because she has combined being the couple’s spokeswoman with writing about them, but says she represents ‘the ordinary person who would never be able to afford professional media representation’ and that she never takes money from interviewees.

But being paid only by the media and not by the source is surely not a complete answer to the point. Detachment and objectivity are no less relevant to conflict of interest here, and Alison Smith-Squire has made her support for Charlie’s parents and their view of the case quite clear in the account published on her own website. In The Times on Saturday 29 July, Alexi Mostrous, the paper’s head of investigations, wrote an article about the publicity campaign and its series of protagonists: Alison Smith-Squire, the Rev Patrick Mahoney, director of the US Christian Defense Coalition, and former UKIP council candidate Alasdair Seton-Marsden. The article questioned whether the publicity had been in the family’s best interests, and quoted Charlie Beckett, professor of media at LSE as saying

There’s a good reason why PR and journalism are separate. If the PR person is also writing stories that does cross a line.

This view has been echoed by the Chartered Institute of Public Relations. Alison Smith-Squire herself published an angry open letter in response to Alexi Mostrous, complaining of his “ill-conceived, ill-judged investigation” and calling it “a nasty little story”. Her response here to the suggestion of conflict of interest is

All you kept saying is was I paid for writing articles where I interview my interviewees. You inferred there was something wrong when this is surely something journalists do every day?

Again, this seems not to meet the point that a person who acts both as “your own trusted publicist and writer” cannot also be an objective reporter of a story. The “Our last hours” story published in the Daily Mail on 4 August was under her byline, but did not refer to her instrumental role in making the story public in the first place. According to the Chartered Institute of Public Relations

Readers of a newspaper story should know whether it has been produced by a person who is independent of the story they are writing about, or by someone representing their client.

UPDATE 23 August 2017: On 14 August Alison Smith-Squire published a blog post headed “Exposing the PRs who jumped on the Charlie Gard bandwagon” and criticising the president-elect of the Chartered Institute of Public Relations and others in the PR business for “using tragic Charlie Gard’s story to promote themselves”. In this post, Alison Smith-Squire says

I am a journalist. Journalists expose issues. Thus the Gard family came to me in the hope that I would help them expose their situation with GOSH. I did that by writing about their situation and doing their interviews – which is what journalists do.

If they’d gone to a PR then a PR company would have charged them fees. Even if that PR acted for free, many PRs actually take money from the press to allow their client to be interviewed (PR is not known as the ‘dark side’ for nothing). Even if that PR acted for free and didn’t take any money for putting them up for interviews, The Gards would have found themselves speaking with a strange journalist who might have written something they didn’t like.

A lot of people seem up in arms about this. How dare Alison Smith-Squire write what the Gards wanted about them (ALL copy is always read back for full approval of all interviewees). But had the Gards been faced with talking to a staffer on a paper, guess what, they wouldn’t have spoken to anyone. So everyone, you would have had no interviews at all to read!

On her own website, Alison Smith-Squire describes herself as a “media agent”. Again, the statement in her blog post that “I am a journalist” doesn’t answer the question of objectivity for a journalist who is also a media agent promoting a story on behalf of clients and in their interests. Nor does it answer the question of editorial balance on the part of the newspaper which publishes the story without explaining the dual roles.

On 7 August, the UK Press Gazette reported that Charlie Gard’s parents were to complain to the press regulator IPSO of the way that the Daily Mail’s exclusive interview of 29 July had been “lifted” by the Sun over that weekend, and quoted Alison Smith-Squire as saying

the newspaper’s coverage had been an “extraordinary binge” on the original piece and that the Gard family had “suffered deeply disturbing, threatening and horrifying online abuse” as a direct result of the title’s “vile actions, vile stories and vile headlines”.

Private Eye has continued to cover “the story of the story”, publishing an article describing a “bidding war” between the Mail and the Sun for exclusive rights to the continuing story, and a further article on 25 August, in which it referred to the IPSO complaint and suggesting that

IPSO may want to query [Alison Smith-Squire’s] assertion that “[Charlie’s parents] have never spoken to the Sun about their story”. One might as well say that they have never spoken to the Mail either: they talked to their spokeswoman, who was then paid for articles quoting them – and who seems to have forgotten that besides her many pieces for the Mail she also contributed to the “vile” Sun.

Private Eye’s article gave some examples of occasions on which it said the Sun had published stories under her byline and paid her for quotes and pictures for which she was credited.

We will post an analysis of any decision ultimately made by IPSO on the complaint.

UPDATE ends

In the 29 July story, Charlie’s parents are quoted as saying they do not regret going to the media, a step they took entirely under Alison Smith-Squire’s guidance:

We were absolutely desperate, and the media was our only option. We lost a lot of our privacy and have coped with the nastiest online abuse so that we could raise valuable issues – and not just for us.

The article continues

A particular low point was when GOSH put out a statement saying doctors had received death threats over the case. It went out the day after Chris and Connie had made their heart-wrenching, but not yet public, decision to let Charlie go. They say they have never spoken badly of GOSH themselves; that their plight was hijacked by some to push their own agenda.

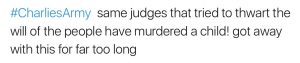

The abuse of GOSH staff, lawyers, and Charlie’s parents has obviously been the most negative aspect and undesirable consequence of the legal transparency and public attention the case has received. Dr Ranjana Das, senior lecturer in media and communication at the university of Surrey, has published via the LSE Polis blog some of her research on the violent and negative impact of the language used by campaigners to vilify the hospital and the provenance of this extremist negative language in the USA rather than in the UK. Abusive language has also been linked with imagery such as swastika flags in a way which would be illegal in Germany and some other European countries.

The increasing extent to which news, press releases and public discussion about the case have themselves become part of the conflict and in the foreground of the story of the case is surely also unwelcome, both because of the risk of a promoted narrative being presented as news, and as a burdensome distraction for both parents and hospital from the more important and sombre tasks of decision-making and care of a child at the end of its life.

Transparency in future cases?

Unsurprisingly, there has also been continuing debate about the principles and practical considerations of transparency, privacy and publicity in legal disputes involving the serious medical treatment of children, particularly where, as here, the child’s identity is made public in connection with a fund-raising campaign for medical treatment. It is perfectly understandable that parents would want to do this: a name, a picture and a real life story are more likely to make a positive appeal to generosity than an anonymised individual. Among the the best-informed and most relevant commentaries that I have found are:

Restoring balance to “best interests” disputes in children, an article by Professor Dominic Wilkinson in the BMJ. His analysis mentions and balances the full range of reasons for and against public hearings of cases of this type, and draws attention to the fact that public discussion about the case was inevitably unbalanced because not all of the medical details were in the public domain. He says

The court of public opinion is surely the worst possible place for ethically complex decisions.

He suggests that

where a court has allowed parents and children to be identified, and particularly if there is already public debate about a child’s medical treatment, it may be in a child’s best interests to make available some of the evidence and argument underpinning professionals’ decisions.

There is obvious sense in this. One disclosure which might have been informative in this case is the transcript of the experts’ meeting on 18 July, which would have formed part of the evidence if there had been a hearing of it on 24-5 July. But, like any information put into the public domain, there’s a risk it could be used in ways which many people would think distasteful and wrong. In Charlie’s case, some fragments of medical information (MRI scans) found their way into the public domain and were used by campaigners, even attached to protest banners outside court during hearings, as described here – protests at which the “army” accused the doctors of lying and “medical murder”. I think that if disclosure of medical information was made in future cases, it would have to be with some restrictions on the way it could be used.

Louise Tickle wrote an article in the Guardian headed “Charlie Gard’s case shows why our family courts must lift their secrecy”, with a journalist’s experience about the inhibiting effect on journalism of reporting restrictions in cases heard in private in the family courts more generally.

In a Transparency Project post Lucy Reed analysed the children’s serious medical treatment cases which were the subject of this article in the Guardian. Reading those which have been reported in the form of published judgments with anonymised names, it’s trite to observe that each case and each family is different, but there are also striking similarities. These are deeply affecting stories of individual children facing the end of short lives, whose individuality emerges from the reported judgments despite anonymisation, and of the desire and determination of their parents to make choices other than those proposed by clinicians as being in their child’s best interests. None of these stories are well-known through press coverage or publicity. There’s no reason why these published decisions could not have been reported in the media, even if reporting restrictions would have limited ‘live’ coverage of the hearings in the way described by Louise Tickle, and anonymisation would have prevented the publication of photographs and other identifying details to link the facts with the protagonists in a way that gives the public a deeper sense of connection with them and interest in their story.

Exceptionalism and public understanding

The absence of coverage of these cases outside the medical and legal professions leads to an individual case like Charlie Gard’s being reported in the media and discussed in social media in a way that gives it undue exceptionalism, rather than a proper context for understanding it and the ethical issues raised in it. This means that the story is presented and understood in a naïve fashion as something entirely unique, rather than as an example of an agonising series of personal and clinical decisions and conflicts of beliefs about best interests, that has occurred in the past, and will unhappily do so in the future for as long as children suffer life-limiting and terminal illnesses.

What has been exceptional about Charlie Gard’s case has been the global reach and rapid spread of public interest in it. This interest grew after the first decision of the High Court in April 2017 had been exhaustively and unsuccessfully appealed by his parents, and, following the interest in it taken by the Pope and the President of the USA, in the lead up to and duration of the further application to court in July. As our 1 August post explains, that application did not end with a full judgment on the evidence, because Charlie’s parents agreed over the weekend of 22-23 July that no further treatment had any prospect of success, and explained to the judge on 24 July that they were no longer seeking a reconsideration of the April decision. As GOSH’s counsel stated in the hospital’s written position statement prepared for 24 July:

Charlie’s parents believe that his brain was not damaged, that it was normal on MRI scan in January and that treatment could have been effective at that time during the months that followed. There remains no agreement on these issues. GOSH treats patients and not scans. All aspects of the clinical picture and all of Charlie’s observations indicated that his brain was irreversibly damaged and that NBT (nucleoside bypass therapy) was futile. Those were the Judge’s findings in April, upheld on appeal in May and on further appeal in June.

Many people reading the judgments and position statements that have been published, will be persuaded by the hospital’s and Charlie’s guardian’s analysis of the evidence which would have been further considered and subject to detailed judgment on 24 July if the dispute had continued. In other words, they accept that the hospital was right to regard further treatment for Charlie as futile when it first did so, and that the suggestion or speculation of some possible improvement in his condition through experimental treatment by the US expert, Dr Hirano, was not made with the benefit of full medical information which would have informed his view differently. There is an interesting scientifically-informed discussion of whether his proposed treatment might have helped in this PLOS DNA Science blog. But it’s clear from the continuing public discussion of the case that there are people who are not persuaded, as well as people who are not prepared to read the primary source material available to inform themselves and make up their own minds, but have taken up a position on the basis of little or no knowledge of the case – something the judge himself commented on and criticised in his 24 July judgment. During the hearing on that day, GOSH’s counsel is reported to have said

Greater transparency has not led to a greater understanding…

Cases that tell stories that people want to believe

In 2011 Theresa May (then Home Secretary) told the Conservative party conference that human rights law resulted in

an illegal immigrant who cannot be deported because, and I am not making this up, he had a pet cat…

The FT columnist Michael Skapinker in a 2011 article (£) used this as an example of

what happens when partial versions of legal disputes become embedded in people’s minds

and observed

The most memorable cases endure because they tell stories that people want to believe.

This is no less true here, and for understandable reasons. People want to believe a story in which a much-loved child who is desperately ill with a rare genetic disease can be cured, and the more credulous will resort to belief in miracles to support this. It’s also a story which has been appropriated, as Melanie Phillips and others have described, by groups of people outside the UK who have their own political or social aims and agendas – in particular Republicans in the USA who support the repeal of the Affordable Care Act, and “pro-life” conservative Christians in southern and Eastern Europe and Latin America, readily conflating the withdrawal of life-support with euthanasia. Closer to home, it’s a story of which newspaper coverage has been led, via Alison Smith-Squire, in the Daily Mail. Its presentation has been consistent with the Daily Mail’s approach to some other stories of people involved in family law and Court of Protection cases, as a human interest story of ordinary people helplessly engaged in a fight against parts of the medical and legal establishment, a fight not just as to whose view of Charlie’s best interests should prevail, but as to whether parents and not the court should have the ultimate right to make best interests decisions when doctors and parents disagree. It was depressing – if not entirely surprising – to find one supporter making an explicit connection between this case and the Daily Mail’s notorious “enemies of the people” headline last year:

There is a lot more to be said about how some of the public interest in the case has adopted this strand of populism, and of ignorance and hostility to the rule of law in our courts. I will write about this in a further and final post on the case.

Featured pic: Endlessly Repeating 20th Century Modernism by Josiah McElheny, image (c) Barbara Rich

So much information and debate seems to do nothing but muddy the waters. the Real issue the public were so concerned about was that the parents should have had the Right to decide the Fate of their child.

they should have been allowed to try the treatment if the wished.

the state should not have taken their Rights away and took complete control of this child to the point of making him their Prisoner.

the Public know it was wrong and they always will.

I think you are right that there was public sympathy for the parents to the extent that many thought they ‘should have been alowed to try the treatment’ despite the evidence.

However, it’s unlikely that the general public believe all parents always have ‘the right to decide the fate of their child’.

The State did not take away any rights from the parents in this case.

Parents do not own a child and under law prevailing in UK and most related countries they have the rights needed to discharge their responsibilities to the child. They generally do so lovingly and appropriately and their views must carry a lot of weight. They generally do carry this weight in Paediatrics, as most of us recognise that the parents will love the child better than we ever will.

So when a centre such as GOSH takes such a strong view and when the parents take such a strongly opposing view the question which arises is “why”. Such situations are very unusual and often turn on information which is private and should not be known to outsiders.

Given this, it is distressing to see how everybody seems to have piled in with their clear vision of the rights and wrongs of what is clearly a very difficult situation, in which we can’t know the key facts as they are none of our business.

This is the sort of situation in which we should all show a little humility, butt out and let those most intimately involved with it work it out. Those using the situation to promote their own political or moral agenda are beneath contempt