Training and resources were the key themes to emerge at last month’s fund-raising Family Law Breakfast, marking Support Through Court’s 25th anniversary, with a panel discussion about trauma in the family courts. The event on 21 January 2026 was hosted by Charles Russell Speechlys in London and supported by OurFamilyWizard, Bloombsbury Professional,and etiCloud.

Keynote speech

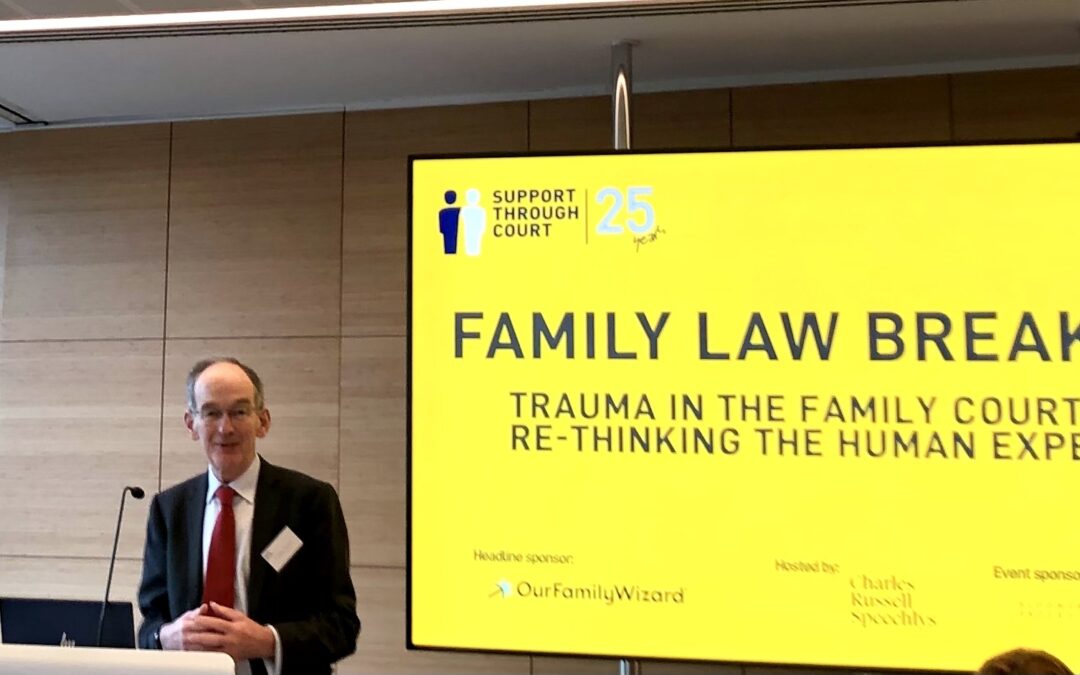

Giving what he said might be more of a ramble than a keynote speech, Sir Andrew McFarlane, President of the Family Division (pictured) began by saying it was right for Support Through Court (STC) to be linked to the subject of trauma, since there was a clear line connecting trauma and stress. In the many cases where litigants did not have the benefit of legal representation, STC helped both those litigants and the courts to manage their cases more efficiently. In a desert where legal aid was not available, STC should be regarded not merely as an add-on but as essential, and ought to be supported by the whole profession. It would only require a small amount from each of the larger firms and chambers to provide the service.

Sir Andrew then complimented Charles Russell Speechlys’ office in Fleet Place for its splendid view, looking towards the river and the continuing construction work on the new courts complex at Salisbury Square. It was hard for anyone working in the existing law courts not to feel a certain amount of ‘building envy’, but he hoped that the new courts complex would allow some space for the big money divorce cases which were just as important to London’s international influence and commerce and would be much better housed there than in the Central Family Court at First Avenue House. The family courts had played Cinderella for too long, and it was hoped that the CFC would be allotted more sitting days for money cases than the 13% allocation (reduced from 16% initially assigned in London, but only 9% elsewhere in the country) alongside the 45% allowed for child cases.

But the main topic of today’s discussion was trauma, something which we might all have felt we knew something about, but which was now much better understood. For example, how domestic abuse could be profoundly damaging without any actual physical injury, through coercive control, and how that could impact on the behaviour of parties in court. The court environment could itself be traumatising for litigants and witnesses. There was a need to understand how to help witnesses and litigants who might be affected by trauma, and the effects of the court process itself.

In this regard, the Pathfinder model was thought to be significantly less traumatising. It should be rolled out everywhere. Currently it was available in ten courts. We were waiting for the Lord Chancellor’s approval of the justice budget for the current year (from April), but it was hoped that he would say yes and that £85m of government funding would be provided over the next three years. Initially it would go to courts outside London, where the focus would be on getting the backlog down.

But that would be a job for Sir Andrew’s successor, after he retired on 1 April. Who that might be he had no idea, nor would anyone else until the candidates had been interviewed in March, before the successful candidate was approved first by the Lord Chancellor and then by the King, some time around the middle of April.

Panel discussion

There followed a panel discussion, chaired by Sarah Higgins, solicitor, of Charles Russell Speechlys, about the main subject of Trauma in the Family Courts, with

- Nicholas Allen KC of 29 Bedford Row,

- Joy Brereton KC of 4 Paper Buildings,

- Dr Sheena Webb, consultant clinical psychologist, and

- Laura Rosefield, former barrister and now divorce consultant.

[Everyone used first names at the event so I’ll follow the same convention here.]

Sheena began by pointing out that trauma could manifest itself in the family courts in a number of different ways. She listed five key contexts:

- In the histories and backgrounds of those who come to court

- In the reasons why they are in court

- In the court process itself

- In things that happened after court

- In the impact on professionals.

Trauma was not a discrete wound but a manifestation of how people react to harm. Exposure to harm impacted the nervous system and affected how people respond to threat.

Laura added that in family law, trauma could affect how witnesses give evidence, it could impact their decision making ability and judgement, their capacity to instruct and correspond with their lawyers, on their ability to parent, and on their general demeanour and ability to cope. It could cause fragmented thinking. She referred to the crippling effect of something called the ‘tsunami of exhaustion’.

Nick discussed how the courts should handle trauma. It was important to remember just how alien the court can feel, especially for clients. Sometimes the necessary arrangements, such as a screen or separate consultation room, were not in place. This could ratchet up the tension. We were all still learning about the real impact of domestic abuse, particularly in relation to coercive control.

Joy said professionals were now more aware of what could constitute domestic abuse. But the court process was inherently adversarial and thus retraumatising. In this regard the Pathfinder was the way forward, ensuring the child’s voice was heard first. But there was room for improvement. The court process was worse for litigants in person, especially if there was domestic abuse, and they wouldn’t necessarily know how to ask for special measures. It was important to ensure they left court feeling they had been both seen and heard.

Having focused initially on how trauma affected litigants, and how the courts could mitigate its effects, the discussion then moved on to how it affected practitioners. This could be in the form of vicarious trauma, compassion fatigue and burnout, or a sense of moral injury, feeling part of a system that was doing harm. There was a danger of shutting down and going cold, or becoming biased. One could not simply keep calm and carry on. Practitioners should watch out for one another and share the load.

Finally, looking to the future, what would a trauma informed court look like? Joy said there was hope in the Pathfinder project, which was recognised as a better way of dealing with cases where there was trauma. Sheena said much could be learned from the Family Drug and Alcohol Courts (FDAC), and the use of a more interdisciplinary approach. Nick added that the increasing focus on non-court resolution was also a good thing, though not a panacea – it had to be safe for the parties who chose to enter into it. There was a risk that parties might seek to weaponise arbitration and thereby perpetuate trauma. Laura said training was critical, for the judiciary, Cafcass, as well as for legal representatives. And we should think about working closer with therapeutic professions.

We have a small favour to ask!

TEN YEARS A CHARITY

The Transparency Project is a registered charity in England and Wales run by volunteers who mostly also have full-time jobs. Although we’ve now been going for a decade, we’re always working to secure extra funding so that we can keep making family justice clearer for all who use the court and work in it.

We can’t do what we do without help from you!

We’d be really grateful if you were able to help us by making a small one-off (or regular!) donation through our Just Giving page.

Featured image: photograph by Paul Magrath, Transparency Project.