Lara Prendergast wrote a piece in The Spectator last week that ran under this headline :

The sinister power of Britain’s family courts – Even if decisions are obviously cruel and unjust, the public is often not allowed to know.

It’s kicked off quite a discussion here at The Transparency Project – no doubt exactly as it was intended to do, with such a big headline. The initial responses of the Transparency Project team appeared somewhat polarised, but following discussion we have reached a broadly consistent view.

It is of course important to go beyond the headline and to drill down to what is actually being said, and what it is based on. There are and some fairly bold assertions in the body of the article, too. Prendergast begins by acknowledging, quite properly, that “It’s right that some children are taken into care.” Others who write under headlines such as this do not do so, so credit for that. The example that Prendergast gives of one such case warranting removal is the recent, tragic case of Ayeeshia-Jayne Smith, murdered by her mother and the subject of a Serious Case Review published this week. Prendergast is wrong when she says Ayeeshia-Jayne was “never removed” – she was placed in foster care for a period before her death but returned. Not that such a point of detail makes any difference to the obvious point that she was failed by those who should have protected her – including but not limited to social workers.

But we are interested in this post in what Prendergast says about the Family Courts :

Because of the strict secrecy surrounding family courts, it is often only when these cases arrive in a criminal court that we get a glimpse of how badly some children are let down. But there’s another risk:…it’s all too easy for children to be taken away from perfectly functional homes.

It is often only through criminal proceedings that we see where things have gone wrong – both outside the family court and under its umbrella. But not always. There are many Family Court judgments published on BAILII – some of which are picked up and run as stories in the mainstream media and covered on this blog – which set out in grim detail failures of social work or other professionals before and during the involvement of the Family Court, and faliures of the Family Court itself. An obvious (but exceptional) example, is the case of Poppy Worthington – and it was only through the transparent and careful handling of the family court proceedings that a light was shone on the failures by agencies like the police in properly handling their investigation into her death.

Prendergast refers to a piece she wrote last year for The Spectator about mothers with mental health problems and their experience of the child protection system. Our Julie Doughty wrote about that in critical terms here. She gives three examples of parents who contacted her about their case having read that article, giving a short one paragraph summary of each case before drawing some conclusions.

One of these mothers is reported as posing the questions :

What gives social services the right to scrutinise, judge or intimidate parents who have disabilities, impairments or illness?…why are they allowed to remove children in such an underhand and secretive way, and the parents are powerless to stop it?

There is of course an answer to this : the need for child protection means that we have laws in this country which require social workers and other professionals to scrutinise – and yes to form judgments about – parents with disabilities, impairments or illness. Because, as the first line of Prendergast’s article acknowledged “It’s right that some children are taken into care” and without scrutiny we cannot know whether this child is one of those that needs to be removed. And yes, the law allows that to be done against the wishes of parents – but removal itself should only exceptionally be secretive, even if the court case itself must remain private.

Underlying these reports of the traumatic experience of parents is an important point about the way in which child protection responsibilities are carried out – how do we treat parents, particularly vulnerable parents suffering from illness or disability who have a right to expect support? The account that Prendergast passes on is sadly familiar – whatever social workers are trying to do, and whatever justification they may have for investigating and acting parents feel threatened and intimidated. Part of this is an inevitable consequence of the power imbalance here, but it is legitimate to ask to ask how much of it is due to heavy handedness or a failure to properly support children by supporting their parents. Sadly, the reporting of this account from a parent doesn’t really advance the project of answering that question very far because we have no real way of knowing if this subjective account arises from a legitimate grievance about poor social work practice or is just an expression of unavoidable upset arising from a very difficult situation.

Prendergast acknowledges this limitation, saying

I do not know the answers, but I know that even asking such questions will result in a flurry of correspondence from judges and legal experts who will tell me that the family courts must remain private — they blanch at the word ‘secret’ — to protect the child and the family.

It is undeniable that the (necessary) privacy of family proceedings does inhibit the answering of important questions like these. In a parallel discussion this week we have also experienced this in trying to write in a balanced way about the so-called “muslim foster carers row” – there too the privacy has hampered those who want to know to get to the bottom of whether or not Andrew Norfolk’s reporting was accurate or fair – just as it has hampered Andrew Norfolk in vindicating himself by publishing everything he knows and the sources of it (or, depending on your perspective, it is a convenient shield that allows a journalist to publish misleading facts whilst preventing others from discovering the alternative truth, that a journalist / newspaper has distorted the facts for the sake of a story). It’s always frustrating when things are not black and white – shades of grey make poor headlines and are untidy. People desperately want a definitive narrative that involves a villain and a hero. Sometimes it just isn’t possible. Privacy sometimes mean we get an annoying half story. And probably some half truth in many instances.

Prendergast says that the lack of transparency in family cases “can often lead to abuse of power“. She goes on to assert that

Judges in family courts can withhold information not just for the good of the individuals concerned, but also to conceal their own verdict. As such, family courts can be sinister places where cruel decisions are made. An obviously unfair decision will not necessarily generate a public outcry, because often the public cannot know.

What is her evidence base for this assertion of widespread abuse of power, cruelty and unfairness by judges? It is a view widely held by those who have been through the family courts and come out with an outcome they don’t like – it would be surprising if that were not so. And of course, the irony is that if there is a sound evidence base for these really serious assertions Prendergast would struggle to lawfully publish them. But it is equally true that if judges in the Family Court were the sort of cruel, heartless despots that are described there would be an awful lot more appeals from their decisions heard by the Court of Appeal and published, even allowing for the reality that not every case of injustice will result in an appeal. Perhaps Prendergast is right – but her 3 sketched case studies go nowhere near proving cruelty of even three individual judges. In the first case the court case was ongoing and no decision had been made about removal of a child – for all we know the judge threw the case out and prevented removal from happening. The second involved a mother struggling to represent herself against her far wealthier abusive ex partner – more an indictment of legal aid cuts than a tale of judicial failure. And the third, is the story of an autistic mother who felt discriminated against in her treatment by social services – but no mention is made of the role played by any judge.

Prendergast’s complaint that “an obviously unfair decision will not necessarily generate a public outcry, because often the public cannot know”, is valid to a point. In a grossly unfair case we would expect an appeal to be launched and it would by that means see the light of day. But even where no appeal is launched there is much public outcry – take for example the recent case of a petition to Parliament (and we’ve noticed another along the same lines recently). Much of this public outcry may be in breach of the privacy rules, but it is certainly not consistently prohibited in practise.

Prendergast says that

The readers who contacted me have one thing in common: they have discovered how frightening it is to find your family tangled up in this system… But I do not get the impression that these people are monsters. They seem to me to be decent people who have discovered to their despair quite how much power the state can wield when on the hunt for ‘danger signs’. Behind closed doors, their families have been ripped to pieces.

That is sadly the daily reality in the Family Courts. The intervention of state agents in your home and life, the threat of taking your children is frightening, terrifying. And most of the parents who have these experiences are not monsters, though they may be risky or poor parents, often parents whose parenting cannot be brought up to a good enough standard even with support. It is unfortunate that allegations of intentional cruelty above and beyond the inevitable fear and upset even the best and most sensitive child protection will induce can be thrown out there without evidence to back them up, and just as unfortunate that if those allegations are true a journalist does not have it within her power to fully expose the truth. And it is not just critics – defenders of the family justice system who would say such criticisms are unwarranted in the vast majority of cases have their hands tied in the very same way.

Our discussions prompted by this piece have centred around that tension – we criticise journalists for not covering family cases or for writing about legitimate concerns without being able to substantiate them – and yet the task is so often impossible to perform well. It is easy to say that a journalist who can’t verify their story from multiple sources shouldn’t publish it, but that would itself leave us with even more of an information vacuum. And reliance on routine and uniform publication of judgments as a solution would be naive – the wide variations in practice between judges potentially allows state agencies who happen to fall under the jurisdiction of a non-publishing judge, in combination with standard privacy rules, to hide any poor practice from scrutiny.

How can we resolve this impossible situation without compromising the privacy for children that Prendergast accepts is justified and necessary? It is not even as simple as saying that journalists must just put in the leg work before going to print, because of the resource implications which are difficult to justify from a commercial perspective – even where a journalist seeks an account from a second source beyond the parents they may find that the other parties are unwilling to speak and are either frightened of or hide behind privacy rules. As much as we think that journalists must get better at asking for the other side of the story, those who are asked to verify or dispute an account given by a heartbroken parent should also, we think, have an eye on the public interest. Is it possible in fact to issue a brief rebuttal or set of key facts which does not offend against the privacy rules, and will not identify or expose a child to risk? In some cases we think it would be possible, but it is easier to fall back on the shield of privacy than to grapple with the issue, particularly where there is such an entrenched culture of blame and shame of the social work profession and a consequent fear of tabloid monstering that probably informs the reaction of local authorities asked for comment.

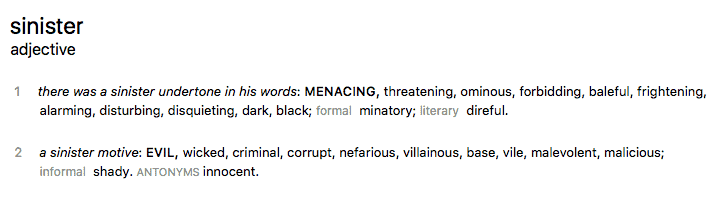

So. Sinister, Secretive and Cruel – A Fair Characterisation?

Well, in the sense that it is in fact frightening for those involved, the Family Court is sinister. With respect to the second sense of the word : that the system or the judges are somehow intentionally malevolent, malicious or cruel – there would need to be a far greater evidence base than we have seen in either this article or elsewhere to make good that proposition.

And secretive?

We prefer the term private to secret, because it properly reflects that the family court is not a hermetically sealed environment. A significant amount of information is made publicly available, the press are entitled to attend hearings and scrutinise (even if for a number of reasons they rarely do). But, as Sir James Munby observed in 2013, “This semantic point is, I fear, more attractive to lawyers than to others” – from the outside looking in the family court probably does appear pretty secretive.

Aside : Louise Tickle, who is quoted in the Prendergast article, is a member of The Transparency Project team. This post was written by Lucy Reed, but approved by other team members in draft.

Feature Pic : The Shadowy Court – (pic courtesy of Mark Hillary on Flickr by creative commons – thanks)

When will the day come where we read more stories of a parent’s battle through their difficulties, crossed many rivers and climbed many mountains and had their children returned, I can only recall one such instance, Annie.

When will we read the positive stories of the professions going above and beyond to help and support parents on their journeys, they do happen, just never reported.

Parents who face the unimaginable are only further disheartened when they read these god awful stories, there is nothing in them that gives out that ray of hope, that chink of a push to prop up and support the parent to continue on their paths of change, a positive story is worth a million negative ones

Ah Jerry, there are some – granted not often, but there are such cases published (though rarely “interesting” enough to be reported). But you are right, a parent or a member of the public could reasonably form the view that all cases end badly and all social workers poor.

As ever, an balanced and considered piece. A few observations from me for whatever they are worth:

1. The original article and indeed this piece to an extent conflate the social work that is done, and the goings on at court / the litigation end of things. I suspect that this reflects public confusion about the roles of the different arms of the state in the Family Justice “system”: court and the Judges are therefore the public embodiment of this process.

I found that the specific issues that I came across were more closely related to everybody else rather than the Judges themselves, subject to three points.

Firstly – I was lucky to be able to afford band 1 rated solicitors and leading counsel, therefore my interactions with the Court were of the very best quality that the Court would expect and be used to dealing with. Were that not the case I wonder how matters would have progressed?

Second – in the “early days” the judges seemed to have their hands tied by (a) either litigation games from the other side (and the inevitable timetabling issues that therefore arose; and (b) their respect for the child protection professionals (about which more later) – they couldn’t act whilst the Social Workers and Police were doing there thing no matter what other evidence could be presented etc. The professionals had to be respected. They could have got a better grip of things and dealt with matters sooner but frankly the demands on their time I suspect are immense and we got there in the end.

Thirdly I am aware of people who came across properly awful judging (and have for example resorted to paying for a full transcript of a multi-day hearing to make the point). These are individuals who are highly qualified professionals in other fields and whom I have no reason to doubt.

2. Transparency (!) is the key to driving out bad behaviour. I would observe that the behaviour of various professionals involved (solicitors: written apology received; social workers: written apology received) was significantly below that which I would expect from professionals – and which I observe from professionals in my day to day working life. This behaviour seemed accepted as pretty much par for the course by my advisors and not worthy of comment and they seemed surprised that I wanted to pursue it.

On thinking about this further: once the litigation is done what private individual is going to deal with the loose ends and issues that arose. I suspect that most litigation ends before hitting baili or a senior court, and it ends with some kind of compromise. Who wants to spend further time dealing with the bad apples and digging through the email / document archive to prepare the points that should be dealt with by, for example, a regulator. Who wants to spend further cash on lawyers to pursue that wayward professional? And I rather doubt that many authorities would want to wash their linen in public and pursue their own workers with the regulator when it turns out they’ve breach the rules.

I am abnormal in this respect: I have the financial capacity to do this, I have a highly regulated job where I am held to the highest professional standards, I pay millions of pounds of lawyers’ fees a year – I know what professional standards are and am appalled when I see a failure. This is particularly so when, during proceedings, I have been told to “respect the professionals” by one of the individuals on whose behalf the social care authority subsequently apologised.

In my working life lawyers and other professionals simply don’t behave in that manner (and if they do then it is followed up).

3. As you note there is an inequality of arms. The Court (on the advice of Social Services) stopped my children seeing me for a while. There was absolutely no support or hint of support for me. I had to fund my own proceedings. Now in my case that was not an issue, but for many…what do you do?

4. Something I’ve pondered as I’ve worked through all of this is – how do you help improve the situation for others – and the answer is a great imponderable. One can seek to obtain statistics from the state to make the point but you are told that those statistics do not exist. But equally you are told in letters from Ministers that everything is working beautifully. When you point out that without data you cannot be sure they studiously ignore the point. How can one make policy without data? The danger is of course that, as highlighted by this charity is that groups with axes to grind create statistics from self-selecting groups to drive an agenda.

The alternative therefore is anecdote – but of course you can’t give the anecdote real strength because the courts are, ahem, private.

Thinking about this in totality therefore: I would argue that the courts are perhaps sinister. They are indeed secret and the justice system does not collect the data to prove that it is working (or not) and prevents the release of stories that might show that it isn’t. This is 2017: it is more than possible to collect the data to drive better policies and better enforcement and all the rest. That it doesn’t reflects badly on it.